Contemporary Portraits: Part One

Greg Thorpe

Image courtesy of Grace Enemaku

This two-part article takes a look at contemporary portraiture through the work of six artists, selected for their diversity of style, approach, subject matter and identity – and because I enjoy their work. Before I wrote about visual art, I wrote about literature, music and theatre – either for money or for university degrees. My training in art writing has been somewhat less structured, consisting of looking at lots of art wherever I go, reading lots of art writing, talking to artists, and learning by doing. Here, for the first time, I’m gently introducing theory to help flesh out my thinking. This was the year I read John Berger’s Ways of Seeing for the first time. I was inspired by his opening essay in which, in pursuit of ‘demystification’, the author considers a pair of 17th century portraits painted by artist Frans Hals, depicting the governors and governesses of a Dutch alms-house for the poor. “Hals” writes Berger, “was the first portraitist to paint the new characters and expressions created by capitalism. He did in pictorial terms what Balzac did two centuries later in literature.” With that in mind, my focus in writing this piece has been to consider who is sitting for whom in contemporary portraiture, who is being imaged and represented by whom, and why? And also, simply, to bring these works to new eyes where possible.

Grace Enemaku and Black Girl Magic

Sorely neglected as a cultural theorist in most fields, including visual art, bell hooks describes how oppressed people “recognize that the field of representation (how we see ourselves, how others see us) is a site of ongoing struggle” (‘In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life’). Image makers are therefore very often involved in a creative push-back against the limiting ways that mainstream culture – including visual art – permits them to be seen, and to see one another. hooks has also spoken about the role of the artist to both reflect experience and imagine new liberatory ways of being which people might witness and will into existence for themselves. The word “imagine” is not an invitation to fantasy or improbability here. Its etymological root is ‘to form an image of, or represent’. In other words, to make art.

This sets the scene for the brilliant (in both senses of the word) work by Nigerian-Irish artist Grace Enemaku, whose ‘Black Girl Magic’ series takes existing portraits of Black women and reconfigures them with adorned hyper-coloured settings that vibrate with unmistakable celebratory energy. The artist selectively accentuates particulars of Black style, beauty and aesthetics in her portraits, for example highlighting fierce nail decorations or dramatically elongated eye make-up which mark the sitters as extraordinary beings. Mixing digital illustration with an almost child-like sticker book aesthetic, Enemaku then surrounds her girls and women with stars, butterflies and crown motifs. The results are contemporary Black female deities, at once real yet celestial, even supernatural.

Within her ebullient aesthetic framework, however, the artist is keenly attuned to the risk of mythologising the strengths of Black women, what theorist Michele Wallace calls ‘The Myth of the Superwoman’. Enemaku tells me:

For 'Black Girl Magic' I was inspired by the idea of the Black woman as a goddess of nature, drawing power from the elements. It’s an image we don’t often see, certainly not historically in paintings or the rewriting of history and religion, so I wanted to do a contemporary take on that. I wanted to give Black women something that says: you’re beautiful, you’re powerful, but also you’re soft and vulnerable, and that’s allowed too. Black women can often get siphoned into archetypes, denying the strength in vulnerability, and denying us the opportunity to be human in a lot of ways. I want to add more versions of ourselves to the visual landscape so more women can look in the mirror and see their features as inherently beautiful because they are Black features, not despite.

Enemaku is in powerful company doing this work. Searching #BlackGirlMagic on Instagram turns up almost 24 million images that seek in multitudinous visionary ways to buck the limitations of image and self-expression for Black women. Asked about her own tastes in Black portraiture, Enemaku cites the glorious images of Lina Iris Viktor:

I became borderline obsessed with Viktor’s work and the rich worlds she creates within them. She is known predominantly for her striking self-portraiture and intricate gilding which gives each piece a life of its own as the light reflects off the gold patterns. Her themes of self, identity and African mythology resonate with me deeply as a mixed-race woman and if anyone has mastered the craft of capturing the Black woman as goddess it is Viktor.

Hobbes Ginsberg and Gender

The timely equation of smartphone camera plus online social media has unexpectedly propelled the self-portrait to be the defining artwork of our era. The things that made this an exciting egalitarian prospect to begin with – democratised access to high quality image-making, the instant expertise offered by pocket tech and image filters, the removal of any social taboos around posing, the sheer profligacy of the selfie – are also what threaten to turn the whole thing into a messy bore. Yet amidst the millions of self-portraitists crowding the ether with new imagery every second, artists still seek out new ways to expand and explore the form of the self-portrait. In this apparent chaos of modern image-making, what is left to the artist who makes portraits of herself?

Hobbes Ginsberg is one artist whose key photographic subject to date has been herself. What began as a readily available method for developing practical photographic skills alongside new aesthetic developments, soon evolved into a new set of meaningful creative expressions for the artist. Ginsberg repeatedly takes centre stage in her tableaux, situating herself in what we might think of as ‘queer interiors’. These are vibrant self-assembled domestic scenes bursting with colour and potentially gendered symbolism, often featuring androgynous clothing or the tender presence of the artist’s own nude and gender non-conforming body, set against various dynamic elements that bring to mind fashion shoots or pop videos. The pleasure and intrigue in the work derives from a combination of these playful colour-drenched settings with the artist’s own inscrutable expressions, perhaps passive or melancholic.

In Self-portrait as reclining nude (Los Angeles, 2018), pictured below, classical art also creeps into the range of visual cues, with Ginsberg’s reclining figure bringing to mind Titian’s Venus of Urbino or its offspring, Manet’s Olympia. The echoes of those earlier reclining figures are queered in Ginsberg’s new setting, yet the sitter is as relaxed as her predecessors, in full contented ownership of her space. Her crotch area remains covered as with the older nudes, but Ginsberg’s subject may be speculatively or even mis-gendered, depending on the assumptions of us, the contemporary viewer. This is a new queer understanding of the gendered nude. To help bring us into her world, Ginsberg dazzles with saturated colour and kitsch floral arrangements. A new aesthetic means new understandings. There is love and safety here too, and even the art-within-the-art of the artist’s own tattoos add pleasurable reference points in skin-deep ways. In Ginsberg’s loud and intricately staged self-portraits we see how a figure might at once be passive and in control, sad yet serene. The uses and pleasures of self-portraiture are revealed to be as necessarily diverse as ourselves, our genders, our own daily emotions.

Image courtesy of Hobbes Ginsberg

Shaun Leonardo and Violence

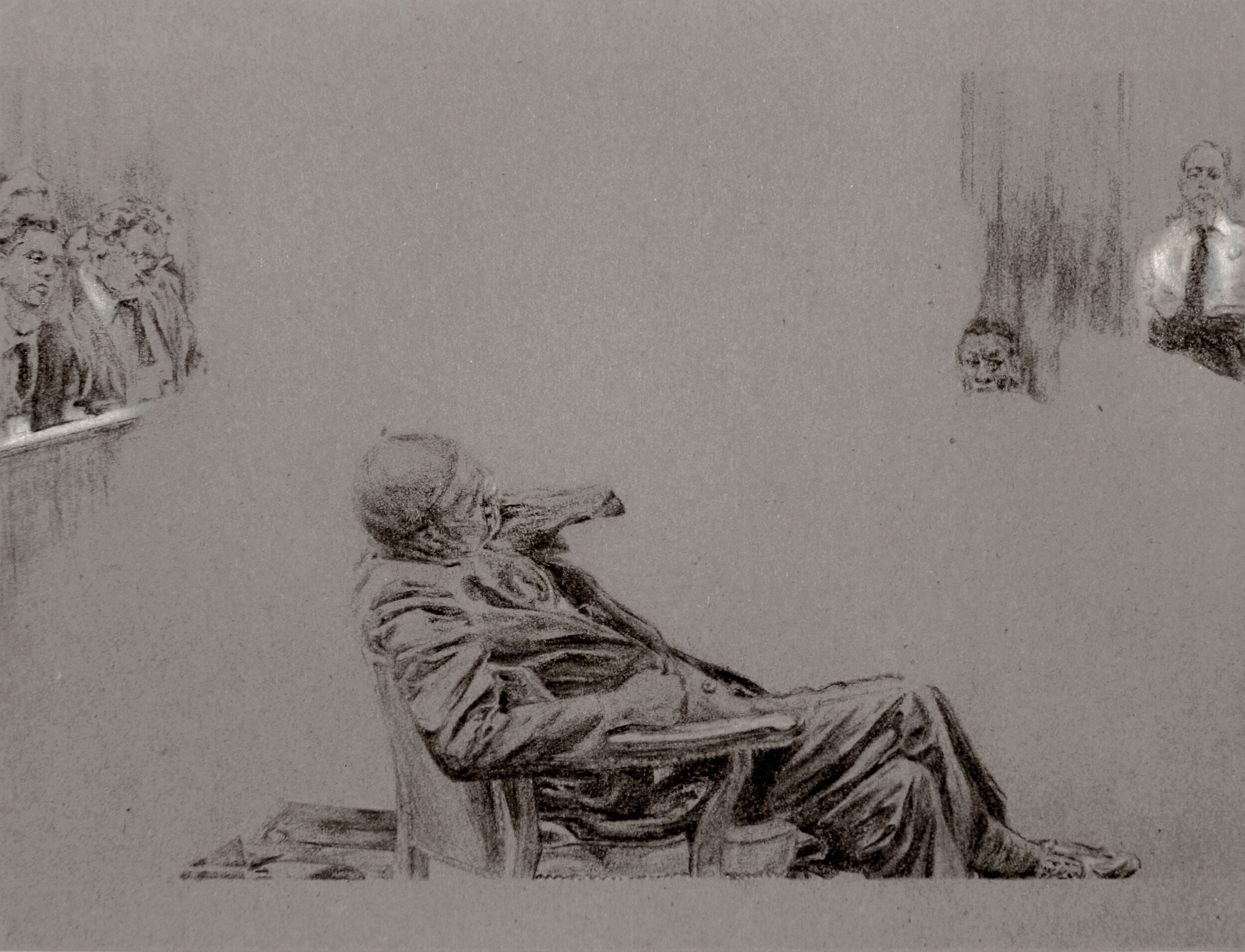

Shaun Leonardo is an Afro-Latinx New York artist whose charcoal works on paper dwell forensically yet cautiously on the lived experiences and violent deaths of Black and Brown men enduring the terror of white America. His portrayals of Keith Lamont Scott, Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Freddy Pereira, Eric Garner and Rodney King – each person a victim of appalling murderous violence committed either by the police or other self-appointed racist vigilantes with the protection of the law – include techniques of fracturing, repetition, blurring, obscuration and omission. This is not a reticence or obfuscation on the part of Leonardo in re-staging these various atrocities, rather it is intended as a set of actions that will hold our attention in deeper, more lingering ways. Leonardo removes from these nightmarish scenes the noise and gaslighting of white America, the too-fast pace of our violent media consumption, and the hyped-up racialised fear in American culture. Ironically, then, Leonardo’s deliberately fragmented, dissected, incident-driven portraiture invites us to look anew at the reality of violence and to look at ourselves and our role and responsibility as witnesses.

Leonardo’s work has fallen foul of the tendency displayed by some of the white gatekeepers of the art world to unconsciously parse all Black experience to a singularity. When Cleveland Ohio’s Museum of Contemporary Art decided to cancel Leonardo’s solo show ‘The Breath of Empty Space’ in summer 2020 they stated publicly that:

the museum was not prepared to support the show responsibly and that its impact could be harmful to our community. These concerns included ethical questions about the representation of Black trauma and death

The artist did feel that he was in a position to do some of this critical expansive work himself but claimed that he was never given the option to do so. The museum then doubled back with an apology for the act of censorship towards Leonardo’s work, admitting it had avoided “difficult conversations.” Black artists are thus caught up in the well-intentioned crossfire of gallery culture in which the politicised artist still occupies, whether they like it or not, a “site of ongoing struggle” described by bell hooks.

The sequence of Leonardo’s works entitled ‘Central Park 5’ (2017) is based on a photograph taken at the trial of five Black teenage boys erroneously charged and subsequently convicted with the rape of a woman in Central Park in 1989. The episode was a grim landmark in the history of racial profiling and injustice in America. A nation witnessed in disbelief as a group of adolescents, whose confessions had been extracted under police interrogation and without proper legal counsel, were tried, convicted and sentenced to prison. Leonardo’s series revisits the scene from the same fixed photographic angle, but each time either figures or backdrops are selectively erased, leaving each of the five young men suddenly set apart. All around them hang the flat expressions of workmanlike lawyers, guards and court reporters, highlighting the dull complicity of the oppressor – men in suits with power to decide the course of other people’s lives.

‘Central Park 5’ is a vital work because it serves to remind us that the law courts and police cells are also sites of racist violence, acting in grotesque harmony with beatings and racist killings, all of which, as bell hooks again reminds us, function as ‘contemporary lynchings’. Considered alongside the expositions of violence that constitute much of his other work, the banality of evil which forms the setting of Leonardo’s ‘Central Park 5’ portraits yields a unique kind of impact. This is an age where images of racist violence can be disseminated instantly and globally to be witnessed in thousands of (re)traumatising instants, yet still no justice served. I have never seen those real-life images and I never want to. But it is in this context Leonardo’s work invites us to pause, to witness, and, in the quiet, to piece together these injustices with our own eyes.

The Breath Of Empty Space will be on view at the Bronx Museum of the Arts from January 21-May 30, 2021. Visit bronxmuseum.org to learn more and for updates on online programming.

Image courtesy of Shaun Leonardo (drawing one of five-part sequence, see two to five below)

In different ways, these three artists might all be said to be making portraiture political, either explicitly and with a focused commentary, or implicitly, by celebrating and centring lesser-seen versions of the self in aesthetically joyful ways. But it is the power of the individual – the literal specialness of one person at a time, and their right to life and a free expression of it – that does the lifting in these portraits. That is the thing I think unites these disparate images. After all, isn’t that what portraiture can do so well? Offer some kind of insistence that we recall how special we are, and therefore how special our life is?

In next month’s article (part two), my focus will be on emotion and sensation, looking at a range of portrait works by Gillian Wearing, Yang Xu and Kareem-Anthony Ferreira.

Read ‘Contemporary Portraiture: Part Two’, here.

Image courtesy of Shaun Leonardo

Image courtesy of Shaun Leonardo

Image courtesy of Shaun Leonardo

Image courtesy of Shaun Leonardo