REVIEW Aug 2024 40 Years of the Future: Where Should We Be Now? Castlefield Gallery, Manchester

David Hancock

Jeffrey Knopf The Closest I Got to Freud’s Desk (2024) Steel, glass and 3D Printed Plastic, installation view @ Castlefield Gallery (Photo: Jules Lister)

Director of PAPER Gallery Manchester Ltd and the Fourdrinier, artist and lecturer David Hancock reviews ‘40 Years of the Future: Where Should We Be Now?’, presented at Castlefield Gallery, in partnership with the University of Salford Art Collection, on show until 6 October 2024, and gives a fascinating insight into the work of the three exhibiting artists: Jeffrey Knopf, Theo Simpson and Hope Strickland.

https://www.castlefieldgallery.co.uk/event/40-years-of-the-future-where-should-we-be-now/

Currently on show at Castlefield Gallery in Manchester is ‘40 Years of the Future: Where Should We Be Now?’, the second of a pair of exhibitions that celebrate their 40th Anniversary. Gathering new works by Jeffrey Knopf, Theo Simpson, and Hope Strickland, all three artists explore aspects of the past within their respective practices, defying the notion that there is a singular world history. In the context of Castlefield’s anniversary, each has been asked to reflect upon and imagine the future, but also to bear in mind alternative accounts of histories that might conflict and be experienced differently by Castlefield Gallery’s audience. The exhibition opened on the eve of the UK’s general election, and after 14 years of Conservative rule the Labour landslide victory inspires hope for the future.

In his digital manipulation of objects, Manchester-based sculptor Jeffrey Knopf is influenced by the theory of Defamiliarisation introduced by the Formalist, Viktor Shklovsky in his 1917 essay, Art as Technique. Shklovsky believed that the purpose of making images is firstly as a means of thinking, and secondly to categorise. He states, “the technique of art is to make objects unfamiliar… defamiliarisation is found almost everywhere, form is found… it creates a ‘vision’ of an object instead of serving as a means of knowing it.”[1]

Shklovsky asserts that we sense an object by how it is perceived rather than how it is known. Our habitual knowledge of an object allows us to ignore it. It might well have never existed. We must, therefore, strive as artists to make objects unfamiliar, fracturing our hold on preconceived notions of the world around us and create ruptures in our understanding, and as such, undertake the process of defamiliarisation.

For Knopf, this act has been personal, born out of the isolation of grief, in which familiar household objects now resonate with the memories of a life once shared. Sigmund Freud expands upon this notion in his 1919 essay on the Uncanny. The etymology of the uncanny is unheimlich, which translates as unhomely. The home is no longer the sanctuary it once was and the furniture and objects around the home take on an uncanny or unfamiliar nature.

In the basement of Castlefield Gallery a red velvet curtain parts to reveal a metal and glass structure centred in the room. Running its length is a crystalline form, an undulating configuration of peaks and troughs. The Closest I Got to Freud’s Desk (2024) recreates the psychoanalyst’s desk from the Freud Museum, London that is out of reach to the public. Knopf’s surreptitiously acquired scan offered an opportunity to further explore these links to Freud in his practice.

Knopf was intrigued by the collection of deities from ancient cultures, which Freud referred to as ‘grubby gods’ that he placed upon his desk. Knopf sees their positioning as a form of barrier between Freud and his patient. For Freud, these objects are both familiar as muses and a source of inspiration, but also defamiliar. They remain inscrutable to the great thinker in their significance to their associated ancient culture, but also in their nature as a crude depiction of the god they each represent.

Here at Castlefield, Knopf’s scan of these deities is manipulated and 3D printed in full length, an incredibly ambitious undertaking. In Knopf’s hands, Freud’s deities are defamiliarised further, their original form only partially recognisable, cloaked in the filament layers that are a result of the 3D printing process. The room is augmented by a scent created exclusively by perfumer, Steven Calver for the exhibition. The scent incants Freud’s office with tones of dust, tobacco smoke, wood fire, musty old books and organic matter. The viewer is transported back to his Hampstead residence through this olfactory immersion.

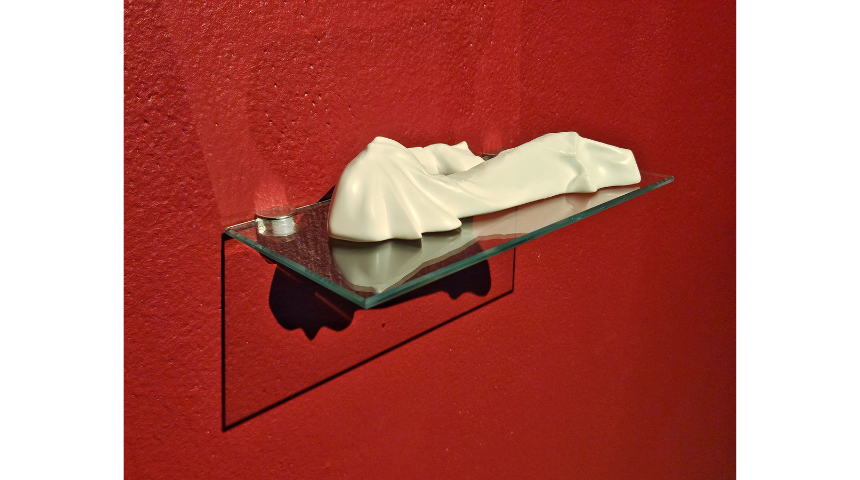

Jeffrey Knopf Couch II (2024) In Collaboration with Emma Lloyd, Jesmonite & Glass (Photo: David Hancock)

A further, related work, Couch II (2024), made in collaboration with Emma Lloyd, sits low on the back wall of the room on a glass shelf. Working from his scan of Freud’s iconic couch, in Knopf’s hands, this eminent object is significantly reduced in scale. The cast jesmonite polished to a marble-like patina, is given the gravitas of a classical form. It is a captivating work, calling out to be handled in a similar way to Freud’s own grubby gods.

Knopf uses his current body of work to place his Jewish heritage centre stage. Global events have placed British Jews in a precarious position. The rise in anti-Semitism on the back of anti-Zionism has increased considerably so that those within the Jewish community fear that they no longer have a voice. As a British citizen, born into a minority religion with a family heritage that is Persian, Egyptian, Polish, and Austrian, Knopf’s Jewishness is integral to his art. An essential reference for Knopf in the positioning of his work for Castlefield Gallery is Freud’s final book, Moses and Monotheism (1939). Having fled the Annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany in 1938, Freud completed the book in London shortly before his death from cancer in 1939. Freud, an atheist, though hounded as a Jew, employed the techniques of psychoanalysis as a form of archaeology to explore the origins of the Jewish religion, whilst questioning the life and death of Moses.

Freud questions his own role in this disputation of Moses, especially as a Jew. Freud’s provocation, aimed at the rise of National Socialism, declares that truth should always be placed before national interests. Given the Nazis’ persecution of the Jews, Freud’s act of profanity in the name of integrity resonates significantly in our post-truth present. There are few living survivors who witnessed the horrors of the holocaust first hand, and this, coupled with the rise of the right-wing, mean the truth is in danger of being forgotten or re-written.

Jeffrey Knopf Companions (2024) Pewter & Glass (Photo: David Hancock)

Knopf traces the inception of another work, The Light Radiates Out (2024), from a flippant comment made directly to him when mentioning his Jewish identity. “Where are your horns?” he was asked in reference to the myth that Jews have horns, which stems from a mistranslation of Moses’ decent from Mount Sinai (The Hebrew word for horn is the same as a ray of light which was believed to emanate from Moses’ head after receiving the Ten Commandments). The work is a scan of a plaque of Moses that belonged to Knopf’s grandfather, Jeff Joseph, who is thought to be the first Persian Jew to arrive in Manchester in 1913, the centre of the global textile industry at the time. With the outbreak of World War I, he was forced to remain in Manchester, making a home and successful business for himself in the Jewish enclave of Cheetham Hill.

In describing his own sculptures, Knopf refers to the process of digital archaeology in their inception. In the rumination of each piece, Knopf also undertakes his own process of psychoanalysis in exploring his own faith and identity as a British Jew; his family history and personal loss; the October 7th Hamas attack and the subsequent conflict in Gaza; and how his work is able to encompass the past, present, and future. Knopf’s defamiliarisation of forms acts to establish something more tangible, filtered through his digital collaging technique. Knopf interweaves these anecdotes around Freud with his family’s narrative of displacement, creating sculptures that further defamiliarise something that already exists as an abstraction.

Jeffrey Knopf Foundation (2024), In collaboration with Angela Tait, Ceramic & Glass (Photo: David Hancock)

In the exhibition at Castlefield, Knopf’s work is split over two floors. The upstairs space contains Foundation (2024): created with Angela Tait, the work comprises renditions of forty Moseses. Each is slip cast in ceramic from a 3D-printed form. Having been scanned and manipulated, they each represent a year of Castlefield, in oblique reference to the title and rationale of the exhibition itself. The grid of Moseses adorn a corner space, whilst facing these, two of their 3D printed brethren stand sentinel over the balcony placed upon corner plinths. The two larger glacier forms shimmer in the light emanating from the large exterior windows of the gallery, their translucency suggesting Knopf’s experience of invisibility.

Theo Simpson Ground Effects IV (2024), layered and pasted single colour silkscreen prints, Installation view @ Castlefield Gallery (Photo: Jules Lister)

Looking past these two works by Knopf, in the lower gallery is an installation of photography-based works by Lincolnshire-based artist, Theo Simpson. As the visitor descends the staircase, Simpson’s collaged fragments of images are wheat-pasted onto the banisters and lintels. Simpson asks us to consider the global impact of humans on the natural world, particularly in light of huge shifts in technological developments and economic forces. We have hit a crisis point, but Simpson’s images neither offer answers nor a critique. They instead reflect our own interpretation of his found imagery, gathered from online auctions, newspapers, books, microfilm, and television. As with Knopf, Simpson trawls the past to offer an insight into the future, re-appropriating and re-energising images to trace the timeline of human evolution that has brought us to this point.

The works themselves are beautifully made. The ephemera displayed within the upper gallery allude to the process of Simpson’s work, a personal archive of sorts, the lower gallery contains the expansion of these elements into something much more fully formed, suggesting both the materiality of the work and how it can be presented. For Simpson, Toward the Metal (2024) has evolved to place less significance on taking the actual photographs, and instead the emphasis is on the experiential process of photography in order for the artist to be present in a specific location. The subjective experience is removed and Simpson, as suggested earlier, allows the images to remain entirely objective.

Theo Simpson Remainder III – Stepping Stones (2022) Layered mounted silkscreen prints / silkscreen printed and lacquered copper bonded in laser cut and pressed 16 – gauge cold rolled steel chassis, 738 x 474 x 15mm (Photo: Jules Lister)

Encased within a frame are a series of 120 x 50mm metal pieces: the spoils of an industrial process gathered over a number of years, Simpson has dry mounted screen printed images upon each offcut. En masse, they can be read as a whole, but each element offers a tiny insight into the fragmentary nature of the world we inhabit. Rust red in colour, they contain a variety of images such as civil unrest, manufacturing, advertisements, natural and man-made disasters, war, and politics spanning decades. The turmoil depicted is never specific. The balance of control and chance are key elements of Simpson’s assemblages, leaving them open to a myriad of readings and interpretations. The nature of these images appear like flashpoints in history, photography bringing these moments to light and fixing them onto paper.

In the final room of the exhibition is the video work by Hope Strickland. I’ll Be Back! (2022) is an absorbing film that captures the Manchester-based artist handling a variety of archival items in conversation with the respective museum curator. Interspersed is found footage collected from the Northwest film archive. Each object is marred by the legacy of colonial violence and resource extraction. One item, a book published by the abolitionist movement, contains the schematic of a slave ship highlighting the abhorrent practice of closely confining slaves for months at sea. The drawing emphasises the slavers’ utter disregard for humanity.

Hope Strickland I’ll Be Back!!! (2022) Digital Video, archival footage and 16mm film, 10’ 58”, Installation view @ Castlefield Gallery. Commissioned by FACT Liverpool (Photo: Jules Lister)

Another collection reveals insects gathered in Sierra Leone by a colonial topographer, Lieutenant Ellis Leach whilst mapping borders and defining British and French territory in West Africa. Each item is discussed in some detail. Strickland draws out the curator’s assertion that Leach wasn’t directly involved in any cruelty to the people of Sierra Leone. This does little to assuage the fact that his geo-political delineation of Freetown impacted hugely on the lives of those living there by breaking traditional trade routes between people and towns, inevitably isolating them from family members and their wider culture. These conversations bring to light the continued trauma that these objects evoke and the falsehoods that Western epistemologies have created that continue to impact upon our lives, highlighting again how the past remains present.

The work is framed by the burning at the stake of Francois Mackandal in 1758 in the French Colony of Saint Domingue (now Haiti). A charismatic leader of the guerrilla Maroons, he was instrumental in uniting the various rebels factions and led raids on the colonial plantations, burning property and killing the owners. It was claimed that he had the ability to shape shift. “I’ll be back!” is Mackandal’s epitaph, his final words shouted to the gathered crowd in Port-au-Prince, witnesses to his execution. As he undergoes metamorphosis, transforming into a winged insect, the viewer understands the significance of the pinned insects shown earlier. Rising from the flames in his escape to freedom, he looks back at his charred remains and swears to continue his reign of terror on the colonial plantation owners for the degradation they brought to his people.

With its roots in Manchester as an artist-led initiative, Castlefield Gallery continues to place contemporary artist practice at the forefront of their programme, providing a voice and platform for those marginalised beyond the mainstream. Castlefield has never been a space to shirk challenging exhibitions, and in their 40th year, they continue to support projects that rigorously question our position in the world.

Footnote

[1] V. Shklovsky, Art as Technique, 1917 in C. Harrison & P. Woods Art in Theory 1900-2000 An Anthology of Changing Ideas. 2nd ed, 2003, Blackwell Publishing, p.280