In search of human spirit – Twinkle Troughton: Remnant

Jo Manby

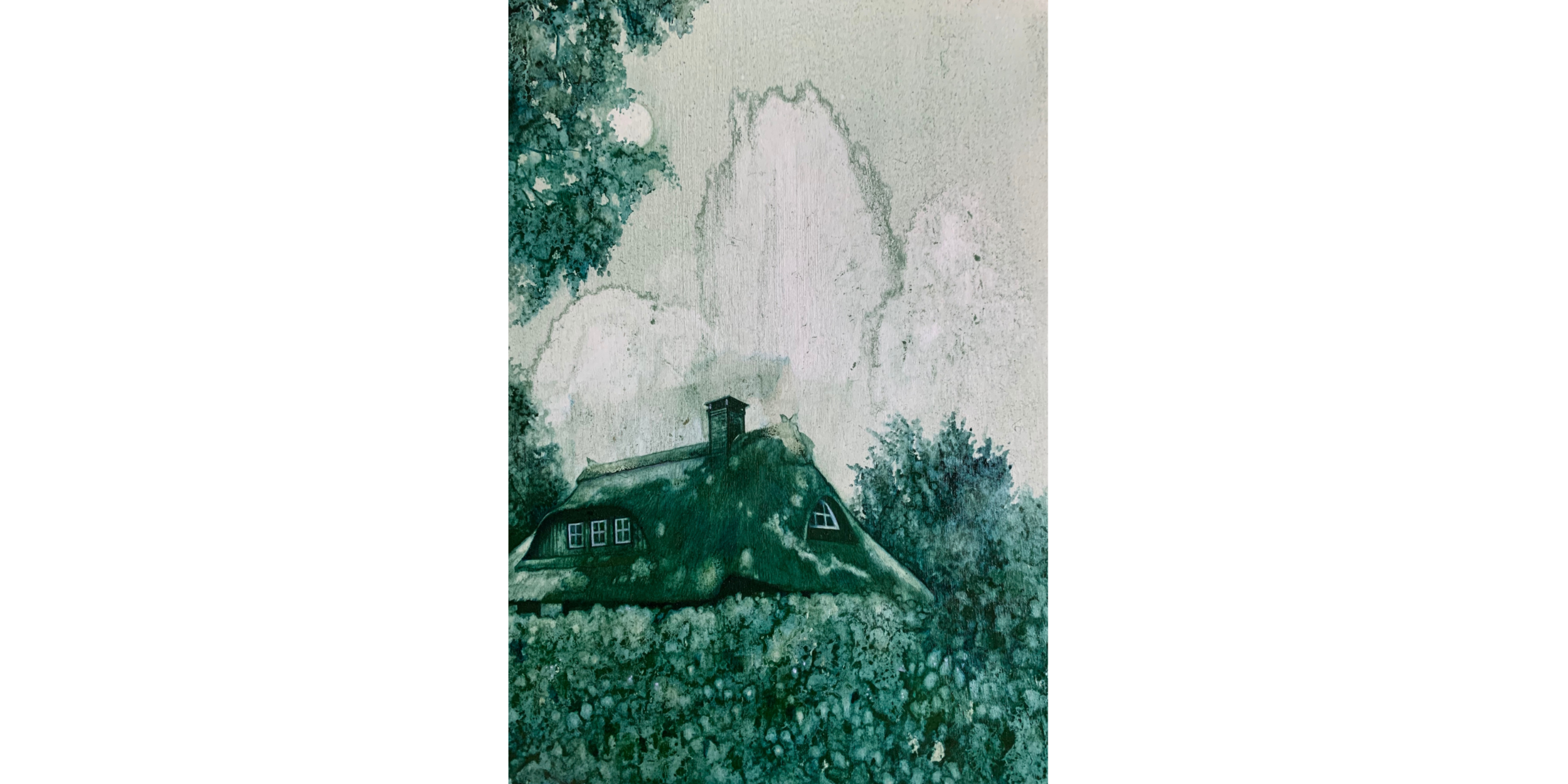

'Windows are the Eyes (das Mutterland)' oil on paper, 15 x 20.5cm, 2019

Jo Manby caught up with Margate-based artist Twinkle Troughton to discuss the mystique of the overlooked and the incidental. This ranges from her paintings of ivy creepers in Margate to the series ‘das Mutterland’, based on photos taken while visiting relations in Germany. The bomb pond paintings depict WWII bomb sites that are being reclaimed by nature and achieving their own miniature ecosystems. Beginning with the quality of the paintings themselves, small and intricate works in oil on paper, the interview delves into some of the secrets and layers hidden in these observations of places and traces left behind in the landscape. Twinkle Troughton exhibits new and recent work in ‘Remnant’, at PAPER Gallery until 30 October 2021, following the previous show of her work, ‘Secrets and Dreams’, presented online 18 April – 15 May 2020.

Jo Manby: I’m interested by your use of colour. It’s as if you are painting in your own version of sepia. How did the green cast to your recent paintings evolve?

Twinkle Troughton: A few years ago, when my practice was focused on imagined landscapes, blues and greens were an instinctive choice as the colours were dreamlike and not necessarily in a pleasant way. Prussian Blue was the basis for most of my work, and still is now, as I can get many different depths and hues from it, from rich and luminous to really murky, at times the murkier the better!

When I started to paint real landscapes such as German homes or bomb ponds, I stuck to the monotone using Prussian blue for the same reason, a dark dreamlike aesthetic. I wanted the paintings to meet somewhere between reality and myth, creating an uncertainty as to whether I had painted from the imagination or not.

Eventually, I began to introduce existing colours from the scenes I was painting, although they are usually slightly ‘off’ to avoid being overly realistic. I started to play with far more subtle twists on reality, and nature’s work can often be incredible enough without having to do much to make the paintings seem slightly unreal. Prussian Blue is still a dominant paint on my pallet even now, a lot of my colours are mixed from it. I like the continuity it gives across my work.

JM: Was German folklore part of your childhood? Were you told fairy stories, and has this influenced your work?

TT: Stories, myth, poetry and fables have all played a large part in my work. In past work, fables such as The Frogs Who Desired a King or The Lonely Wolf by Janos Pilinsky were key influences. I was intrigued by how stories which were decades, if not centuries old were still relevant to modern life. My work has moved on from that now though. I stopped trying to tell other people’s stories, and have been looking more recently at how stories and the imagination can be triggered by the landscapes around us.

Storytelling in the context of Germany was a big part of my childhood in that my nana, who was born in Amsterdam to German parents, would always tell me stories. I don’t recall if they were specifically German or not, although I can’t imagine Germany not being an influence in the stories she told. She took me to Freiburg and the Black Forest when I was 6 years old, landscapes don’t get more fairytale than that!

The stories that influence me more though are real stories told by my nan about her life as a child, pre, during and post WW2. My Great Aunt, my Nana’s sister is still alive, and her stories about their past are enthralling. Life as a refugee, life on the run after their father joined the resistance, taking on new names, eating tulip bulbs for dinner, and there are stories I haven’t been told too... stories that I am not sure I’ll ever find out.

When I last visited my Great Aunt in the small town she lives in called Schneverdingen, the fairytale-esque houses there captivated me. I kept wondering what stories they held, what secrets the walls had seen, who had hidden there, what hopes people had, or who had feared for their lives. The houses look idyllic and slightly mysterious from the outside, and it’s what they hide that fascinates me. And so, from there, I began to look at myth and stories as something we project, rather than doing the storytelling myself.

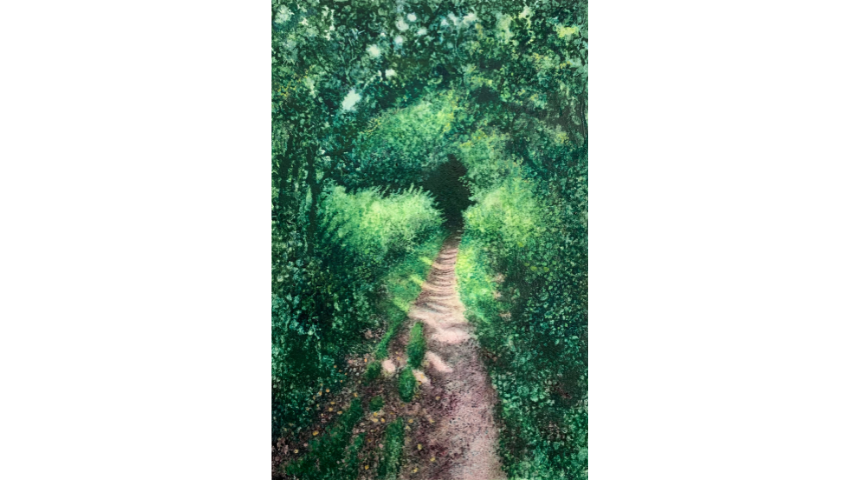

'Footpath V' oil on paper, 15 x 21.5cm, 2020

JM: When choosing a subject to paint, what’s the key quality that you base your selection on?

TT: My choices are based on a variety of things, but I would say the common element running through it all is atmosphere. There is an admiration of nature in my work. Walking plays a big part in my day-to-day life, and if something causes me to stop and pause and wonder, then it becomes a potential subject. It’s often a detail within our landscape, something that might not be seen for what it is, or something that holds traces of history, or remnants of a person’s story. I see my paintings as a pause, a moment of reflection.

I also choose details from our landscapes that look as though I could have made them up, as though I painted them from my imagination. People have asked if the German homes I paint are real or not, and it’s that collide between myth and reality that I look for. And more recently, I have been painting the strange mounds of ivy that grow along our clifftops here in Margate, they really do look like strange otherworldly beings.

The bomb ponds I have been painting are often small unassuming ponds which when you begin to understand how they came to be, look completely different to being ‘just a pond’. Craters in the earth from a violent event which now hold water and life and which on the surface can look tranquil and serene, in total contradiction to their creation. And for me, considering the reason for the pond, I begin to wonder about all the lives affected by that moment in time, who pressed the button so to speak, who was hurt, who survived to tell the tale. The stories begin to form again.

And footpaths... footpaths take my imagination with them. I can’t help but wonder about who has wandered over them, what journey they were taking, who they were thinking about that day. It’s the little stories our imaginations start to conjure from these details which captures me, and which makes me want to paint them.

JM: Is it the idea of place contaminated by historic events or deeds? Or is it more somewhere that evokes a degree of mystery or romance?

TT: It’s both. I don’t want to be overly romantic, which is why I think my work tends to err on the side of dark and mysterious. But it’s the history of that place, even if we don’t know it but can sense it, that is a great lure.

JM: The Sick Lion was an early iteration of your application of fable to social/political issues. Do you feel that with your work on the refugee-related themes of The Lonely Wolf poem by Janos Pilinsky you have arrived at a more integrated, possibly more mature articulation of what is wrong with the contemporary world?

TT: The Sick Lion was my earlier attempt at working from old fables. But by the time I had got to The Lonely Wolf, it was a good few years later and I had realised some of the mistakes and naivety in what I was doing; creating work which assumes a moral high ground can often lead to an echo chamber. Questions became more interesting to me.

The Lonely Wolf was actually a poem that had a personal connection for me. It was a poem my Grandad sent my mum when I was a child, and I remember finding the poem and being so struck by it, it stayed with me for years. Eventually I managed to find it again on the internet after a needle in a haystack search, and the words were just as powerful to me. The poem is about Pilinsky’s experiences as a refugee, and my paintings used that to interpret a world inhabited by a misunderstood and displaced person. But, the words of the poem weren’t my experience, and are likely to be describing a life I’ll never know, so I decided to eventually move away from this. I wanted to stop trying to tell someone else’s story.

However, I think all of this past body of work is what lead to an understanding that my mind works in stories, and while I’m not being so literal about that now, it’s an underlying element in all I do.

'Displacement: Woodland and the Lonely Wolf', oil on paper, 200 x 180mm, 2019

JM: How important is it to your practice to integrate your painting work with your social activism?

TT: It used to be an integral part of my practice. I am by nature a political person (Facebook friends will probably testify to that), and I would always use my art practice as an outlet for my opinions and thoughts on what was going on around me. But now my focus has shifted away from making paintings to make a statement, and I have become far more excited by what is not said than what is. Although having said that, my work does seek to utilise appreciation as a more subtle form of activism, by way of respecting nature.

JM: Similarly, how important is it to integrate painting with performance? Do the two strands complement each other / do they go hand in hand at times?

TT: Two strands definitely used to complement each other with regards to my older work, but I don’t feel there is so much of a link now. I have embarked on many projects with fellow artist and childhood friends Tinsel Edwards where performance and public intervention is used, often with humour and always to make a political point. These events feel like the right time for me to voice my opinions and incorporate direct activism. The most recent one we did was for the Art Car Boot Fair in response to and in objection to Brexit. But that feels very separate to my painting.

‘The Osiers I, Dagenham Park Craters’ oil on paper, 20x15cm, 2021

JM: With the works from the series ‘Das Mutterland’, ‘Bomb Ponds’ and the pathway works, how important to your work is it to make a physical visit to the actual places, or can you sometimes rely on found photographs only?

TT: A lot of my work originates directly on my own experience within that landscape. It's about seeing the right spot at the right time in the right light and having that moment of pause or foreseeing a painting in what I am looking at.

Lockdown is how my work ended up becoming more local, as I prefer to use my own imagery where possible. The Cliftonville ivy paintings have been inspired directly from my experience of passing these mounds regularly and being amazed and intrigued by their strange shape and wondering if others had noticed them too.

I haven’t been able to add much to the ‘das Mutterland’ series due to travel restrictions, as I need to be in Germany for that. So, I have spent time reworking some of my original photographs, looking at how changes in my painting during lockdown (referring more to the actual colours in the image for example) affected the outcome of the work. I have enjoyed seeing the differences. I tried painting German homes from found imagery during lockdown, and the outcome was far less satisfying for me. I am looking forward to continuing with that work as soon as I can, although for now I am planning some more re-workings while I wait.

The paintings of bomb ponds are the odd ones out here though, as they are all from found images. I was planning to visit some of the locations myself just as the first lockdown began, but for obvious reasons I then couldn’t go. And so, I spent time reading up on where the craters were, and how they came to be, and used found imagery to make the work from. The history behind these ponds and a marveling at nature’s ability to heal compelled me to make these works even without my own direct experience of them.

'Ivy, Cliftonville Promenade III' Oil on paper, 21x15cm, 2021

JM: You’ve spoken about your love of painting on paper. So many of your subjects seem to be anonymous places but at the same time places that have borne witness to historic events. Is there something attractive to you in the sense in which with each new painting, you are adding a page of history, another layer of paper, to the massive and disparate archive of historic texts, photographs, maps and drawings that, en masse, document the history of the 20th and 21st centuries?

TT: I do often liken the paintings to being pages from a book, which again comes back to the storytelling. It’s really interesting to hear what others read into the work though, such as what you have described in your question. I am not sure I had thought about my current work as documenting history as it’s not necessarily factual, but perhaps it does in a more ambiguous way.

A lot of my love about painting on paper is directly connected to the act of painting. There is some overlap with the metaphorical qualities, but if I just start with the very basics, I love the physical quality of paper and always try to show the torn edges when exhibiting the work. I love the way the surface of the paper holds stains as I remove paint or add the mediums, the mark making I can make on paper doesn’t happen in quite the same way on canvas. I am also drawn to the fragility of paper; it adds a quality which can sometimes seem temporary and therefore more precious. But there is also an element of sustainability that appeals. I feel like making small paintings on paper is a way of not adding too much extra materiality to the world.