Nasreen Mohamedi: Poetry Within Structure

Laura Harris

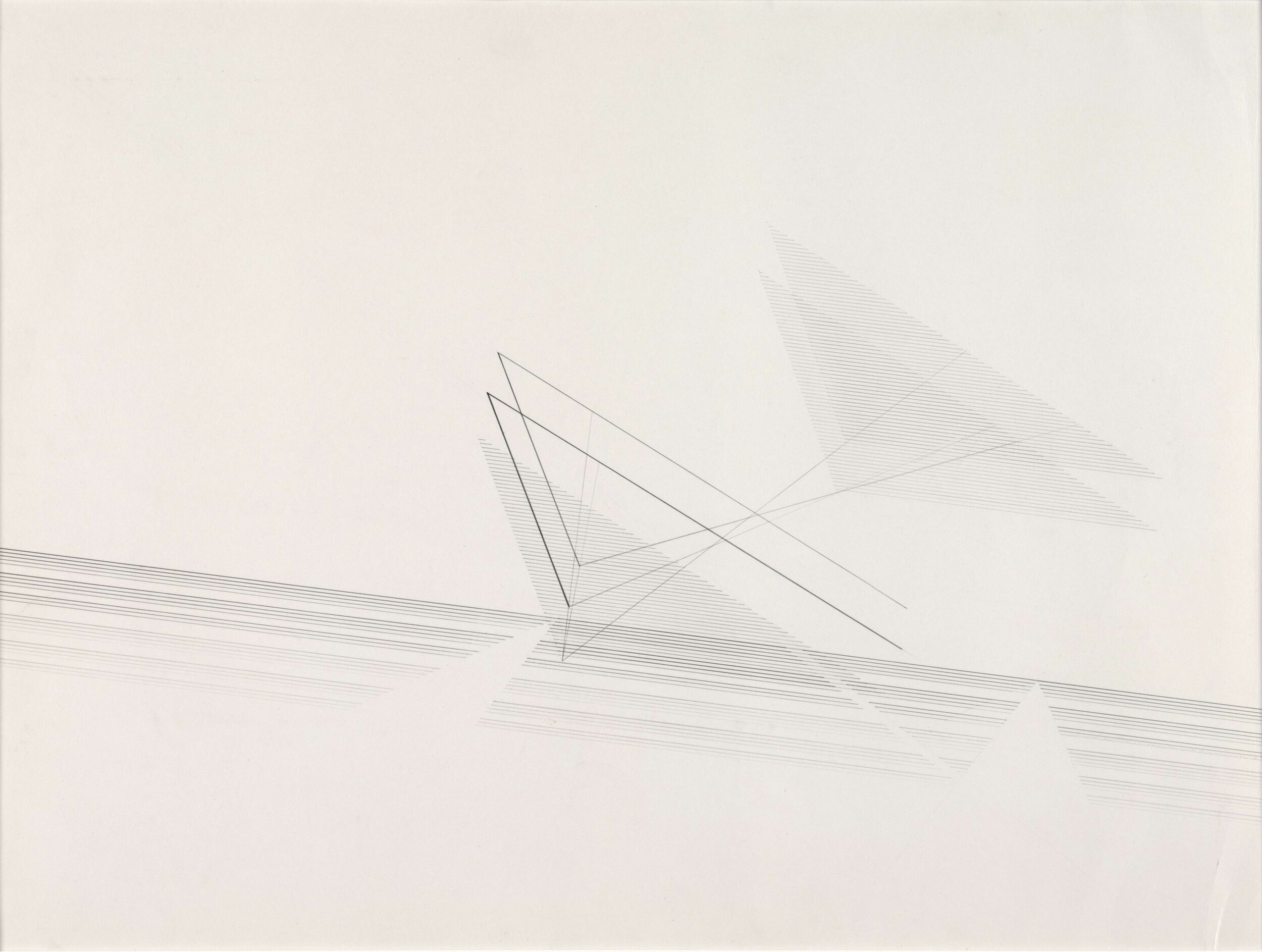

1980 ca. 49.9 cm x 66.3 cm ink & pencil on paper. Collection of Glenbarra Museum ©Estate of Nasreen Mohamedi

Laura Harris revisits the work Nasreen Mohamedi, considered to be one of the most important modern artists from India and whose work has risen to international acclaim since her death in 1990.

At the twilight, a moon appeared in the sky;

Then it landed on earth to look at me.

Like a hawk stealing a bird at the time of prey;

That moon stole me and rushed back into the sky.

I looked at myself, I did not see me anymore;

For in that moon, my body turned as fine as soul.

The nine spheres disappeared in that moon;

The ship of my existence drowned in that sea.

Rumi, Divan, 649:1-3,5 (translated by Fatemeh Keshavarz)

Nasreen Mohamedi (1937-1990) was a fastidious artist. Her art is a rumination on form; light and shade, order and disorder. Across her diaries, photographs, and the drawings for which she is best known, Mohamedi emerges as a woman intensely fascinated with the world as it appeared to her. This came at the expense of any figuration or symbolism. In Mohamedi’s hand, however, austerity and reserve seem somehow charming and rich; the clear result of a lifelong obsession with looking.

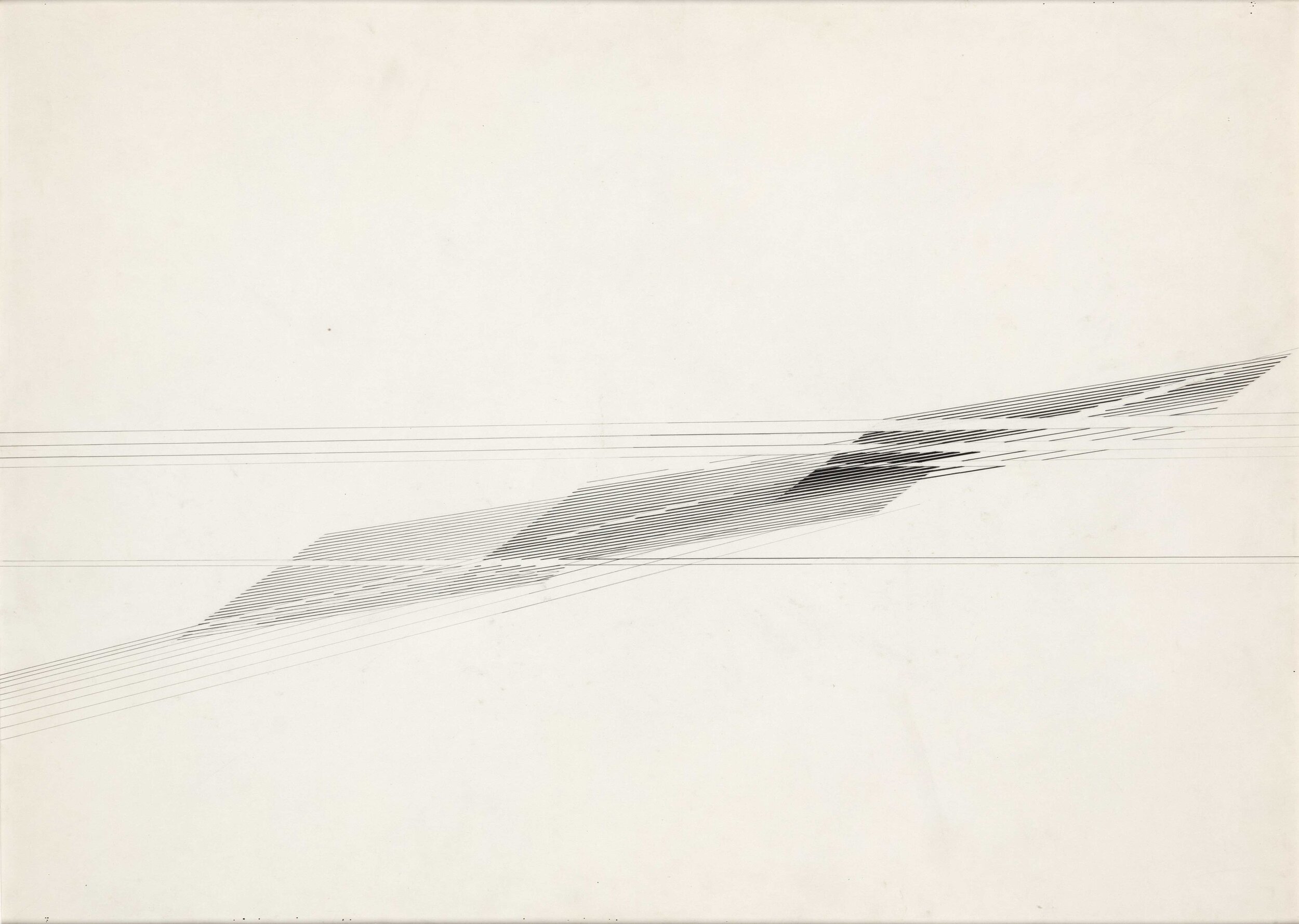

Mohamedi worked mainly on paper, occasionally using grid paper for precision. The tools of her trade were simple: set squares, rulers, and ultra-fine markers with black ink. Obsessively repetitive fine lines almost hover over her pages, while big black shapes sit atop this delicate meshwork. Her drawings are evidence that within tight restrictions a playfulness can be found. Mohamedi creates ‘poetry within structure,’ as gallerist Deepak Talwar writes. This ‘poetry’ comes from playing with dimensions. Often, the image seems to recede into the page. In other instances, it seems like Mohamedi has somehow captured a delicate piece of lace as it floats to the ground.

Nasreen Mohamedi, Untitled, c 1970. Photography b/w, vintage print. Silver gelatin print, 9 x 13.5 in. Credit: Chatterjee & Lal. Image: Heirs of Nasreen Mohamedi

Mohamedi’s photographs are often used to illuminate what she was doing with her drawing, though the artist herself never considered the two art forms part of the same practice. Through the camera lens she captured the shadow thrown onto the ground by a building; the sea meeting the shore; or road markings on a wet day. In these images, the features are more recognisable. It is clear, through looking at them, that the abstraction Mohamedi achieves across all her work is deeply rooted in things she has seen – albeit, things seen as they usually are not; framed in such a way as to render them unusual.

At 18, Mohamedi left Mumbai (where her family had moved from Karachi, now Pakistan) for London, to study at St Martin’s School of the Arts. Her style, however, abounds with influences far more varied than the studious art she would have seen emerging in the 1950s London art world. Returning to India (by way of Paris) after university, Mohamedi’s life was spent in metropolitan and artistic social circles in India or travelling. Her diaries – which provide an extensive source of drawings, quotes, dates and personal reflections – are full of gallery openings and encounters with artists like Zarina, whose art shares synergies with Mohamedi’s. She also took inspiration from poets like Rumi and Ghalib whose poems are spare and cerebral, and whose interest in simplicity and light share much with Mohamedi’s approach. She was interested in weaving, and in the Kufic script; with this in mind, who could not see the calligraphic or woven nature of her lines?

Mohamedi’s social nature is often held up as an important characteristic of the artist, and indeed her social connections populated her life with both friendship and artistic inspiration. She counted Jeram Patel amongst her friends, and though the two had different styles and feels, they both trod a similar line between experimentation and restraint. Looking at the images they produced, you can understand why these two artists would be friends. She travelled widely, especially drawn to deserts, to Islamic architecture, and Zen aesthetics. It is through this social milieu and geographic wandering that Mohamedi’s art is best understood.

1975 ca. 51 cm x 71 cm ink & pencil on paper. Collection of Glenbarra Museum ©Estate of Nasreen Mohamedi

I first encountered Mohamedi in an exhibition at Tate Liverpool in 2014 where she was paired with Piet Mondrian (a somewhat blunt and cynical pairing, I have come to think). There exists, in writing and curating Mohamedi, a need to place her in the terrain of art familiar to European and American audiences. This is no surprise; it is, after all, how canons operate – the ruler against which everything is measured, as much as the whip forcing everything in line.

Mohamedi has been paired with Mondrian in Liverpool, with Agnes Martin at Documenta 12, with Gego at New York’s Drawing Centre, and repeatedly with many more European and American Modernists and Minimalists in articles, book, and discussions. The parallels are clean and too easy: grids, abstraction, austere palettes. These exhibitions have become part of the story of Mohamedi as her posthumous fame has eclipsed that which she experienced in her life. This is the fate of many artists, not least those whose lack of recognition is due to them not being the usual suspects feted by the Western art world.

Since her death, her career has been subject to study and the ‘story’ of her life has been solidified on exhibition walls and catalogues. In a 2016 MET Breuer show, for example, despite Mohamedi rarely signing, dating or titling her work, the curators endeavoured to present it chronologically, imposing a kind of order and regimen. There is, of course, a logic in this, as her early gestural, spirited mark-making is an interesting predecessor of her later reserved and measured gridwork. I cannot help but wonder, however, if this knee-jerk rationalising of her ‘development’ bears little resemblance to the type of logics that Mohamedi was pursuing; as an artist, she was not trying to make the world fall into line, but to throw the world into new reliefs. Perhaps each piece is better met on its own plane, as a rumination – a short poem – on a certain slicing of light and dark.

Mohamedi spent much of her career teaching at Maharaja Sayajirao University. True of many artists, it is, I think, important to recognise her as a teacher. The contemporary structure of the art industry sees many artists also working in universities, and the nurturing of young artists deserves its place in the annals of art history. Somehow, this seems to particularly fit the image of Mohamedi that emerges from her work – dedicated and precise, playful and attentive; the hallmarks of her drawings are the hallmarks, too, of a good teacher. Her life was cruelly short, but, like all teachers, she undoubtedly left a legacy in those she taught.

Mohamedi makes stillness, simplicity and reserve look easy. As Sonal Khullar says of her work, however, ‘stillness was always a matter of effort.’ The almost peacefulness of her drawings betrays a life of labour, looking, abstracting and condensing. We are left with her slant on the world, and her invitation to find patterns and rhythms in our lives as we live them, in the world as it appears to us.