Foday Kabba: Where do we go from here?

Sara Jaspan

Courtesy of Foday Kabba

“People say a bird should be in a cage so it doesn’t fly away and get eaten by predators – that’s how we look at ourselves sometimes. We put ourselves in a prison.” – Sara Jaspan speaks to Salford-based artist Foday Kabba ahead of an upcoming solo exhibition of his work at PAPER Gallery titled, ‘Where do we go from here?’ (12 September-24 October 2020). Find him on Instagram @the_namesfoday.

A fragment of face – just the eyes and nose – is raised upward by leggy metal supports, like an offering to the gently billowing, Van Gogh yellow sky. A midnight blue ground rests below like a deep, meditative sea.

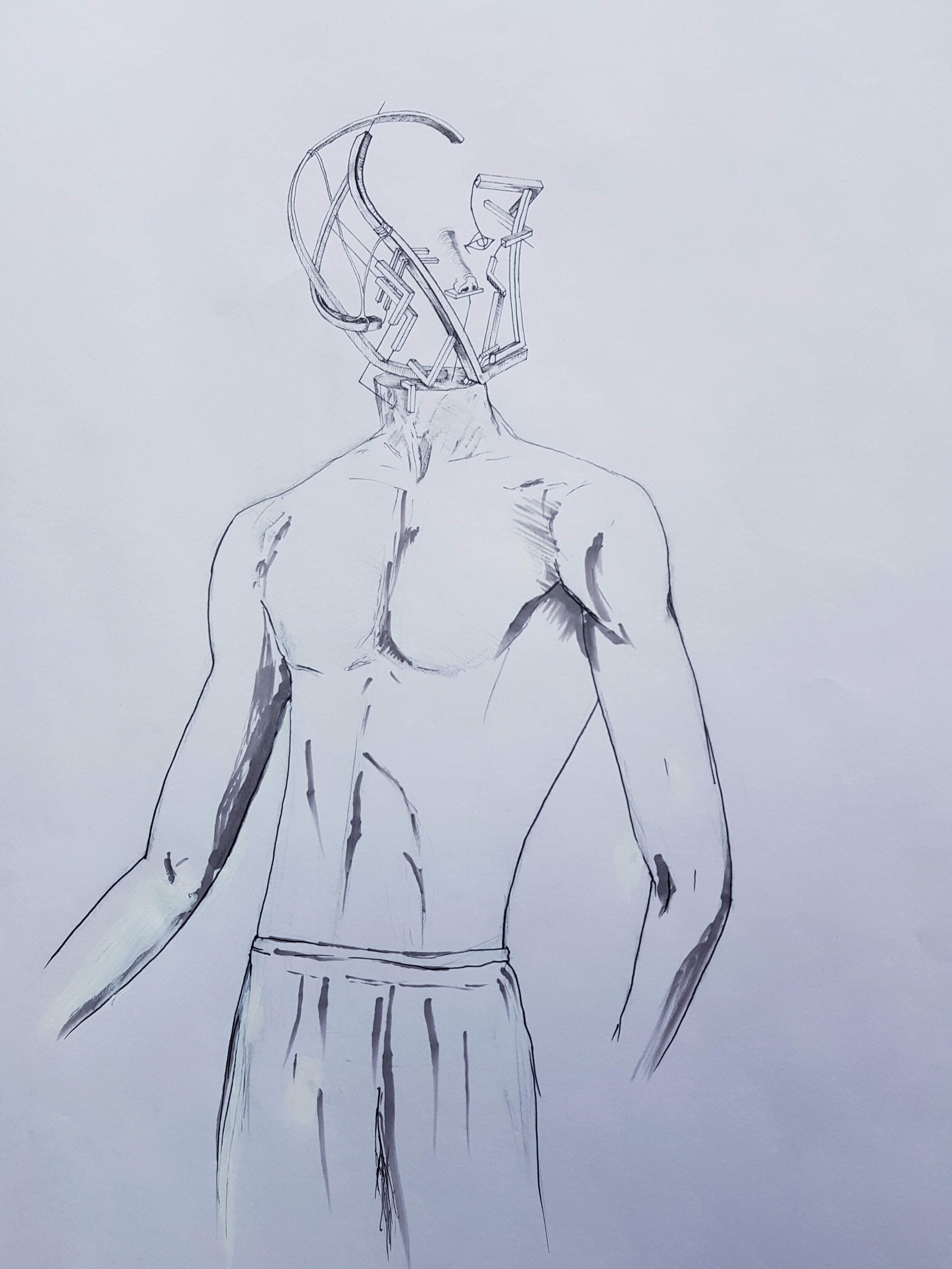

An athletic torso, abruptly severed at the neck, gives way to the rough beginnings of an eye and nose, encircled by a complex framework of curved beams, ropes and lines.

A languid eye drops from the pinch of a spindly white hand amidst a floating circus of parts that together form the vague outline of a head. A grate of some kind hovers above. The background has a celestial quality, beginning in rosy-red hues then bleeding into a vivid blue.

***

Over the past few months, the pages of Foday Kabba’s sketchbook and the tiles of his Instagram have begun to fill with a curious set of ink drawings and acrylic paintings. Surrealist portraits, of a kind. Heads in cages, was my first, rudimentary thought, along with a vague call back to the eccentric contraptions of the 20th century American cartoonist Rube Goldberg. Piecemeal faces peer out from behind surrounding layers of scaffolding, caught in a midway state of construction by an autonomous assembly of cranes, winches, planks, ropes, beams, architectural lines, staircases and prodding, coaxing, cajoling hands. Scrolling through, these works have the direct quality of automatic image-making; of having fallen unfiltered from a mind granted the freedom to wander. Kabba draws incessantly – on the bus on the way to work, in his room at home, in all the in-between moments.

Courtesy of Foday Kabba

The surrealists, Salvador Dali in particular, have a lot to answer for. But travel further down the snaking grid of posts, or deeper into Kabba’s personal matrix of influences, and a more complex narrative emerges. A painting by Wyndham Lewis crops up, as well as a photograph of Pablo Picasso in his studio in Cannes, 1956. The uniquely strange ‘pod’ portraits by George Condo are also mentioned when I speak to Kabba via Zoom (how else these days) from where he lives in Salford. Condo’s description of his own work as a kind of ‘psychological cubism’ seems too useful a term not to grasp hold of here. But also, Kabba’s love for the towering monoliths and more modest-sized metallic labyrinths of the 20th century Spanish sculptor Eduardo Chillida are an essential reference point.

Kabba’s drawings and paintings about the nature of identity, explored through space. They began in three-dimensional form with a series of wire and steel sculptures that he developed during his time at the University of Salford and which became the centrepiece to his Fine Art degree show in 2018. Heavily influenced by Chillida, these works gave the impression of pure abstraction, yet in fact lay closer to portraiture – within the spindles and metal bars were faces, there to be seen by anyone willing to look; to move around and view things from a different perspective. It was only the loss of access to the welding workshop and studio space at Salford upon graduating that led to the continuation of the series on the surface of the page.

What is it about Chillida’s sculptures that so captured Kabba? “The fluidity,” he explains. “But also, I feel like I’m looking at a piece of maze. I like his use of mass and architectural space, especially with his smaller pieces. I like how you have to wander around them to get a better understanding of what you’re looking at.”

It’s the multi-dimensional, maze-like complexity of a human being that the conversation moves to. Just as in his cubist works Picasso would draw a face from different angles to capture its features and the nature of perception more completely, Kabba is interested in portraying something of the many different sides or parts of the self, of our internal reality, and, in turn, of how we “construct ourselves” for others. “I meet so many people that seem like they’re just projecting what they think others will like,” he says. “We never ask: Who are we? Where do we want to go? What are we learning? Instead, we chain ourselves to others.”

Courtesy of Foday Kabba

I ask about the ‘cages’ or scaffolding that seems to enclose the faces in his drawings – to corral the features into some semblance of order. Are they sinister or protective? “Both. If you’re trying to figure yourself out but you don’t want to be vulnerable, you trap yourself. People say a bird should be in a cage so it doesn’t fly away and get eaten by predators – that’s how we look at ourselves sometimes. We put ourselves in a prison. There are so many people with mental health issues these days and part of that is to do with how we lock ourselves away and hide who we are. We never truly express ourselves.” The tendril-like shapes sprouting out of the blue-blazered figure in Kabba’s most recent post represent our ‘inner demons’. “I see them as parasites – all the things inside of us that shouldn’t be there.” Hands, meanwhile, have the ability to point, silence, pass judgement.

It is only in Kabba’s very latest work that colour has begun to creep back in since his time in the print room at university. The tones are bright, bold, expressive. They are something he wants to use more of, specifically as a counter to one particular societal demon: fixed notions of masculinity. “Because of the whole masculine thing and locking yourself away, it becomes very difficult to be colourful,” he reflects. “And when I think of colour, I think of expressing joy, of showing different emotions.”

Courtesy of Foday Kabba

One beautiful acrylic painting that stylistically interrupts the flow of the others on his Instagram is a more traditionally representational portrait of Oluwatyin Salau, the 19-year-old Black Lives Matter activist who was found dead on the 13 June 2020 after she was kidnapped, raped and murdered. I don’t ask Kabba about this work; it speaks for itself as a powerful tribute and mark of respect made toward another human being, civil rights advocate and Black person. It carries a great deal of emotion and expression.

While some of Kabba’s black and white drawings have a somewhat cooler, more removed feel than his paintings, emotion remains far from absent and many of the captions associated with each post, such as ‘personal distancing’, ‘chaos is upon me’, ‘my imaginary fortress’, cement this. It seems art itself is a sort of ‘safe space’ for the artist. He describes: “We have our thoughts and there are times when my mind just wants to fly away; go different places, to a world where they don’t exist. I could just go there and be by myself. But those places don’t exist, so I make them, I draw them.”

Courtesy of Foday Kabba

What’s next for Foday Kabba? In the short term, he wants to continue to progress this current body of work, experimenting more with colour and pushing his ideas further. Looking into the future, a return to sculpture is the ultimate goal and perhaps a studio in which to work. For now, though, a selection of his newest drawings is about to open at PAPER Gallery under the title, Where do we go from here? (12 September-24 October), marking his first solo exhibition. The question posed by the title feels apt not only for our particularly uncertain, Covid-ridden present but also for the condition of society more generally over the last few years. Like so much as we emerge from life in lockdown, I look forward to finally seeing his work IRL and up close, in the way it deserves, rather than mediated by the pixels of a smartphone screen.

‘Foday Kabba: Where do we go from here?’ runs at PAPER Gallery in Manchester from 12 September to 24 October 2020.

Courtesy of Foday Kabba