Psycho-Geographic Painting – Jasmir Creed: In Conversation

Jo Manby

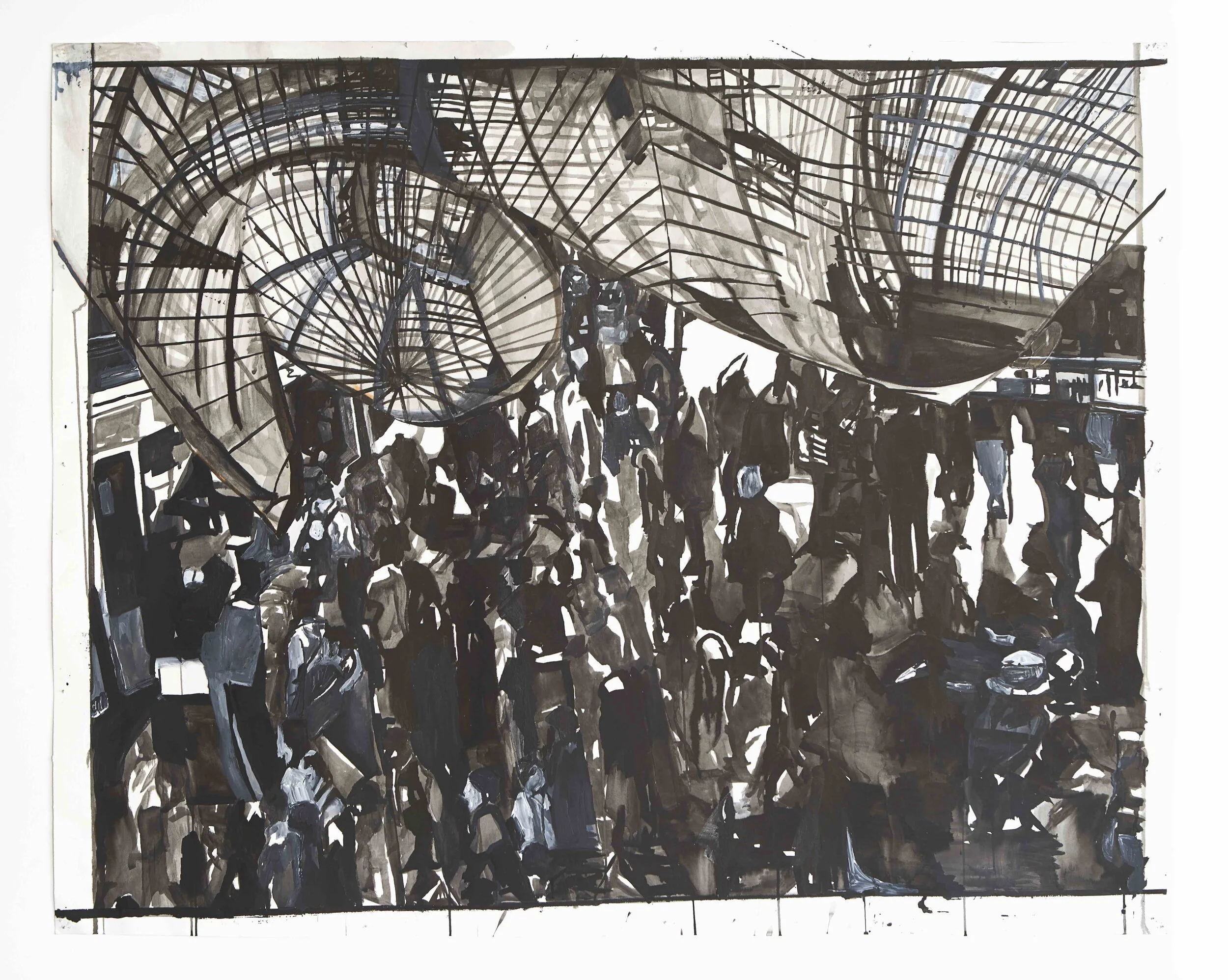

Jasmir Creed, Hope Rise, 2019. Acrylic and ink on paper 150 x 120 cm

Manchester based painter Jasmir Creed graduated with a BA and MA from Wimbledon School of Art in 2015 and is just beginning a practice-led PhD at the Slade School of Art in London. Over the last few years, she has honed her identity as a female urban wanderer, inspired by the poet Charles Baudelaire’s construct of the flâneur as a strolling observer. She is constantly reacting to the cities she inhabits in the form of paintings and drawings, which are often based on montages of found images, photography, and more recently, film footage.

Jo Manby: Looking back, can you identify what it was that first sparked your ongoing psycho-geographic journey? When was the first time you looked at the surface of the city and saw a psychological space beyond it that you could then explore in painting?

Jasmir Creed: I began closely observing my immediate environments when I was at UAL Wimbledon College of Art in London (2010-2015). I spent time studying specific sites, such as the space in front of St Paul’s Cathedral where people lived in tents in 2012 as part of the Occupy London protest. I have since continued to be fascinated by sites of events, including political protests, and non-places like road traffic interchanges.

As a visual art practitioner, I am drawn to sites like Manchester Victoria Station and the Imperial War Museum North because memories such as of death and conflict are present and referenced there (relating to the Manchester Arena attack in 2017 and the upheaval of both World Wars, respectively). These group memories leave ghostlike remnants in my own and other people’s minds of events that have happened in both recent and past histories.

I consider my canvases and works on paper to be my own psycho-geographical terrains of dislocated scenes I encounter, with paint and ink acting as my mapping tools.

JM: Could you tell us more about some of the places/architecture in Manchester that you have responded to in your work?

JC: My painting Hope Rise (2019) was made in response to the terrorist attack at Manchester Arena above Victoria Station three years ago. In it, I reference the sculpture from St Anne’s Square – a main city centre site where a memorial parade and gathering took place in 2017. The title of the piece refers to a feeling of hope after devastation, while its bright colours capture the almost celebratory feeling of people’s spirits collectively rising above the tragedy. I use the paint thinly, referencing the idea of spirits metaphorically rising from the dead.

Whilst painting Hope Rise, I was inspired by a poem by the Manchester poet Tony Walsh called ‘Mightier than War’, which explores the triumph of the human spirit during times of conflict after people came together to support those greatly affected by the bombing. I heard the poem whilst observing the Big Picture Show projection at the Imperial War Museum North. Quotes that stood out included: ‘Imagine all those faces from the history books’ and ‘with that spirit, human spirit which is mightier than war’.

I reference the Imperial War Museum North in my painting Nocturna (2018) and the museum commissioned another painting by me in 2017 in which I responded to its collections, which I also invigilate. I am fascinated by how the building’s aluminium cladding represents a globe shattered by the conflict caused by wars, and how its architecture (designed by Daniel Libeskind) enhances the museum’s subject matter, with its sharp angles, sloping floors and leaning walls unsettling and disorientating visitors.

Jasmir Creed, Nocturna, 2018. Oil on canvas, 215 x 150 cm

JM: Thinking of the way you have described the fluidity and dynamism you find in working with ink on paper, how formative was your residency at PAPER Gallery in 2016? To what extent is paper involved in your current practice, as a support, a medium or a mode of preparation?

JC: The residency led me to start producing large scale works on paper exploring the short journey between the gallery and Victoria Station, responding to architectural, spatial, historical and cultural qualities through montage. In particular, the work explored the Green Quarter district and how dilapidated and regenerated areas of architecture contrast.

Producing new work and generating dialogues with the team at PAPER enabled me to develop ideas for future projects. It was also invaluable to discuss my work with visitors every Saturday whilst the gallery was open. I experimented a lot with different drawing processes and ways of displaying my work in the space I had.

My drawing Steel Webs from 2016 shows a crowd at Victoria Station integrated and powerless within the station’s web-like architectural lattice of stone and concrete aerial tracery, serving as a metaphor for capitalism with its movement of commuters. The works I produced at PAPER formed my solo exhibition Urban Forest at Delta House Studios in London in 2017, which explored the city as a rich forest-like environment that straddles both the known and the unknown, dense with architecture, traffic, people and activity.

Jasmir Creed, Steel Webs, 2016. Ink on paper, 150 x 120 cm

Paper also plays an integral role in terms of the construction of my photographic montages. I produce montages by hand rather than digital software as I am keen for an audience to see the relationship of the artist’s hand interacting with the material. The texture of the very thick, large paper I work with is firm and relatively non-porous, allowing for a sense of translucency in my application of ink when drawing huge swathes of architectural structures over the surface.

JM: Can you tell me a bit more about your work with collage and photomontage, and more recently, found film footage?

JC: The use of chance in my work is an important factor in its production, based on experimentation with montage using photographs I take and collect combined with drawing and painting. My montages use surrealistic juxtapositions through which I form visual dialogues to create senses of observed experience.

JM: You’ve spoken about being influenced by the reimagining of the urban environment by writers such as JG Ballard, Italo Calvino and China Mieville, and the films of Godfrey Regio. I love the way your work feels as if parallel worlds are being ripped up and stuck back together in a kind of visual version of sci-fi. What can you do in your paintings on paper and canvas that can’t be done in fiction or cinema? I guess painting is your medium and that’s why you do it, but what can you reveal to your audience that other art forms cannot?

JC: I paint because the materiality of the medium resists whatever my intentions are, and the work never comes out the way I plan for it to. Hence, painting creates a hugely exciting journey for me. Painting is like solving a puzzle where visual elements such as colour, shape and line work together in coherent ways to express an idea or an emotion about combinations of things I see, remember and imagine. There is an intimate connection between the artist’s hand, eye, mind, brush, and the colours in paint.

Jasmir Creed, Spirals, 2017. Oil on canvas 100 x 55 cm

JM: Do you ever aspire to be involved in filmmaking in some way, either now or in the future?

JC: I am keen to start using filmmaking as a source material for my paintings and drawings. I intend for films to be part of my artistic process and also works in their own right. Film is time based, with people and objects in constant states of movement. I convey a lot of movement within a static image which has taken time to produce, so painting is also time based in a way and takes time for the viewer to look at.

During my PhD at the Slade, I am planning to research sites in London that form part of the Crossrail project. The Crossrail is causing changes to the landscape and cityscape, creating shifts in narratives about history and physical materials along its route. Battersea Power Station is part of the scheme and I am fascinated with how lecturer and writer Timothy Morton describes the station as a ‘post-industrial Stonehenge’ as it slowly comes into view as trains leave Vauxhall Station. He mentions there is a feeling of the eerie where ancient horsetail plants grow between the train tracks, illustrating how natural forms come to life at different times.

I will possibly film a journey of me walking through the Crossrail sites and I do not know exactly what I will find. I have made short films before of my travels on the London Underground, at Waterloo Station (which I filmed by pointing my camera at the ceiling as I descended the escalators) and on a train from Manchester to London (by angling the camera downwards at the train tracks as the train was travelling very fast). I wanted the viewer to have a feeling of disorientation caused by the distortion of camera angles.

Over the course of the PhD, I will also document and investigate physiological and psychological responses to city crowds, random pedestrians and political protesters. I will do this via my on-site drawings, photography, filming, sound recordings, and reading of material such as text and film archives in museums, libraries, on the internet and social media to further understand individual and collective responses.

JM: Have you made any new work for your forthcoming solo exhibitions Utopolis at Warrington Museum and Art Gallery (autumn 2021-winter 2022) and Metropia at Dean Clough in Halifax (autumn 2021-winter 2022)? What else are you planning for your PhD? Do you have a line of inquiry already, or are you still working your way towards it?

JC: Both exhibitions will entwine notions of utopia and dystopia in new paintings, expanding from my solo show Dystopolis at the Victoria Gallery and Museum in Liverpool (2018-2019), and addressing the physical sites surrounding the galleries, including their relationship to historical and contemporary cultural changes.

For example, I recently completed a painting titled Coronight (2020) in which I explored the effects of Covid-19 within the industrialised landscape of Halifax. It shows women of South Asian background huddled together wearing masks. The Saville Fountain (a sculptural fountain in the Western Classical style located in the town centre) can be seen behind them, in front of the nearby Piece Hall – a former 18th century northern cloth hall that is now a museum and shopping complex. I am considering the Hall’s architectural design and human interactions, such as the transcultural in terms of the historic and contemporary migration of people from South Asia, alongside the ongoing trade in cotton and textiles between the UK and South Asia stretching back to the British Empire.

Jasmir Creed, Coronight, 2020. Oil on canvas, 130 x 120 cm

My painting March of Peace (2020) is based on the decommissioned Fiddler’s Ferry Power Station in Warrington, where I am exploring heterotopic composites of imagery reflecting time displacement. The image of Fiddler’s Ferry is contrasted with an image from the Victorian era of a crowd at the Warrington Walking Day Fair. I painted the figures in layered thin washes of monochromatic blueish black, showing a ghostly, eerie presence of the past crowd amongst the industrial architecture of the power station today.

In another very recent painting, Unwired (2020), I created an invisible map of an anonymous woman’s thoughts and background. This canvas shows muted colours reflecting the drabness of a train environment, contrasting with a monochromatic crowd of people flitting in and out of each other at a station. The theorist Michel Foucault considers trains to be heterotopic space as they operate like portals between alternate worlds in fantasy stories. One reason to linger in a portal is to give an audience the enjoyment of being transported to another world or place.

For my upcoming PhD I will explore the uncanny, the eerie and heterotopias based on my psycho-geographic urban journeys. I plan to develop new imagery representing juxtapositions of incompatible spatial and temporal elements in architectural sites that I see as domineering and dystopic for people traversing the metropolis. This will integrally link with my writing and to theoretical and contextual material on contemporary art, the urban, and the socio-political, including tensions between the individual and the corporate.

The two central questions I will address are: ‘How can the uncanny and the eerie translate into my painterly exploration of urban journeys and the structure and nature of crowds, such as commuters and protest marches?’ and ‘How is heterotopia in urban and virtual spaces explored aesthetically in contemporary painting, including in my own art practice?’

Visit Jasmir Creed’s website here.