‘It is not an image I am seeking’: 60 years of drawings by Louise Bourgeois

Greg Thorpe

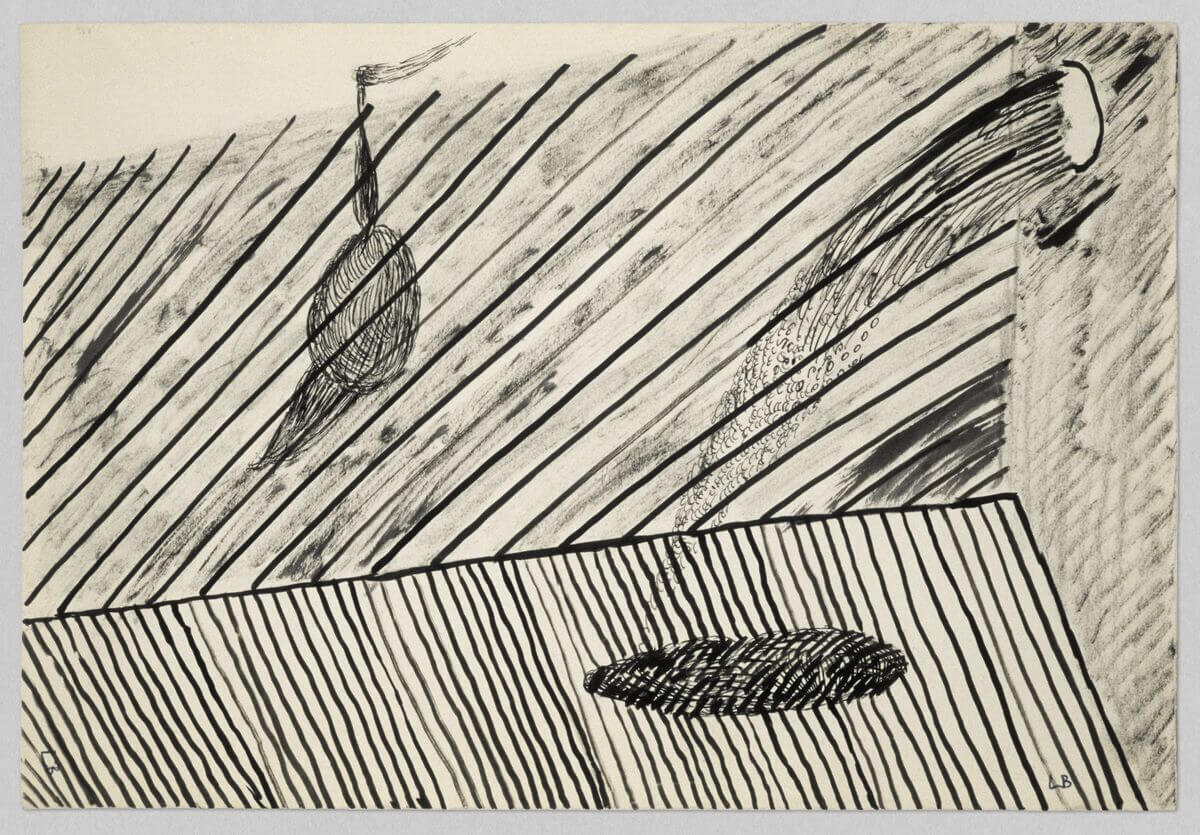

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 1970. Watercolor and charcoal on paper. Image courtesy of Hauser & Wirth

Greg Thorpe explores a series of 14 drawings made between 1947–2007 by the legendary 20th-century artist, Louise Bourgeois, presented as an online exhibition by international gallery Hauser & Wirth. Find Greg’s timely sister-text on Bourgeois’ sculptural work, Quarantania, I, here.

“Louise Bourgeois’ work has been so deeply embedded within my heart since I was a teenager. After seeing a collection of her ‘Cells’ and works on paper, something ignited inside – a sensation of being and feeling human; melancholy, repulsion, joy, desire, curiosity. Themes that I would quickly see evolving and continue in my own drawings as my art practice developed. Her works resonate just as strongly with me today as they did then.”

Rachel Goodyear, visual artist

“I am in absolute admiration of her as an artist. The work I have seen of hers, for example the retrospective at Tate Modern a few years back, blew me away in its sensitivity and human tenderness. And Louise Bourgeois as a woman, as an artist, is an inspiration; how she kept going her whole life and, almost like a fine wine as the saying goes, she just got better with age. Will I still be working when I'm her age? Still compelled to get out of bed every morning and create. To comment on the human condition and channel my life experience and vision into my practice, to reach out and make connections with others in such a touching way?”

Sarah Hardacre, visual artist

The long life of Louise Bourgeois, from 1911 to 2010, represents the real span of the 20th century as we understand it; the era of mass industrialisation, industrialised violence, and the violent revelations of the unconscious. Bourgeois’ 20th century was forged in the Great War, and it expired, in yet more grotesque explosions, on September 11, 2001. Bourgeois was an infant in France during the former and a New York City octogenarian by the latter. The turbulent century had followed her around. Bourgeois’ era also saw the birth of the ‘individual’, a mode she had prefigured, being always proximate to but somehow never fully a part of the multiple artist movements that ebbed around her. Artist Antony Gormley has described Bourgeois’ work as a lifelong project in “finding form for our anxiety” and in that sense – as anxiety persists into the 21st century as our defining experience – Bourgeois is also an indispensable voice for this century too, even in her absence.

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 1951. Image courtesy of Hauser & Wirth

Those who love and understand Bourgeois the most are others like her; she is the artist’s artist, exemplified by the generous testimonies I gathered for this article. Bourgeois would hold regular artist salons at her home until close to her death, demanding to know the impetus and reasoning behind the various works offered by each generation behind her. A look at our most celebrated recent art movements will almost always reveal traces of her influence. She was manifest throughout the work of the Young British Artists, for instance; in Tracey Emin’s textual stitching and subject matter, in the statues and genital preoccupations of the Chapman Brothers, in Sarah Lucas’ post-feminist punning, and in multiple works from Rachel Whiteread, Damien Hirst and Marc Quinn. “It is not a torment to be an artist, it is a privilege,” Bourgeois once chided another artist, even as she herself produced some of the most tormenting images in the lexicon of modern art. Her subjects included sex, exile, betrayal, misogyny, suicidal impulse, guilt, and motherhood; her mediums and materials were every bit as varied.

Maman (1999), the most famous and largest of Bourgeois’ nightmarish Gothic spider sculptures – and perhaps the last great artwork of the 20th century – was in fact a tender tribute offered in love; a gigantic arachnoid metaphor for another beloved weaver: her mother. Things aren’t always as they first appear to us in Bourgeois’ world. This is true of much of her output, down to the smaller works on paper that often underpinned her creative thought processes or expressed the unmediated subconscious shapes of her insomniac mind. Emin, her eventual artistic collaborator, described Bourgeois’ collected Insomnia Drawings, made between 1994-95:

These are not patterns, these are not shapes, these are coming from the inner space inside her psyche, and all she’s doing is showing us what they look like, and that’s what’s so amazing about them.

A selection of the artist’s drawings from a 60-year span makes up the ‘inaugural online exhibition’ from international gallery, Hauser & Wirth, displayed as a simple navigable page on its website. ‘Louise Bourgeois: Drawings 1947–2007’ consists of 14 digital scans of her works on paper and cardboard, variously composed in ink, pencil, watercolour, charcoal and/or gouache. Each one is shown in full alongside an accompanying detail, cropped by the gallery. There is no option for zooming in to the image yourself, other than with whatever function your own laptop might offer. All 14 of the original works have been rendered at roughly the same size on the site, so there is no sense of relative scale between the pieces. (In reality, they range from 19 x 28 cm up to 60 x 48 cm in size.) Underneath each image is an undated quote from the artist which pertains, sometimes directly and sometimes obliquely, to the work pictured. The exhibition is Hauser & Wirth’s first foray into a new digital focus – a direct response to the post-COVID cultural landscape – under the title ‘Dispatches’, described as ‘a new series of original video, online features and experiences that connects you with our artists as we continue to navigate our shared reality together.’ The works are all for sale.

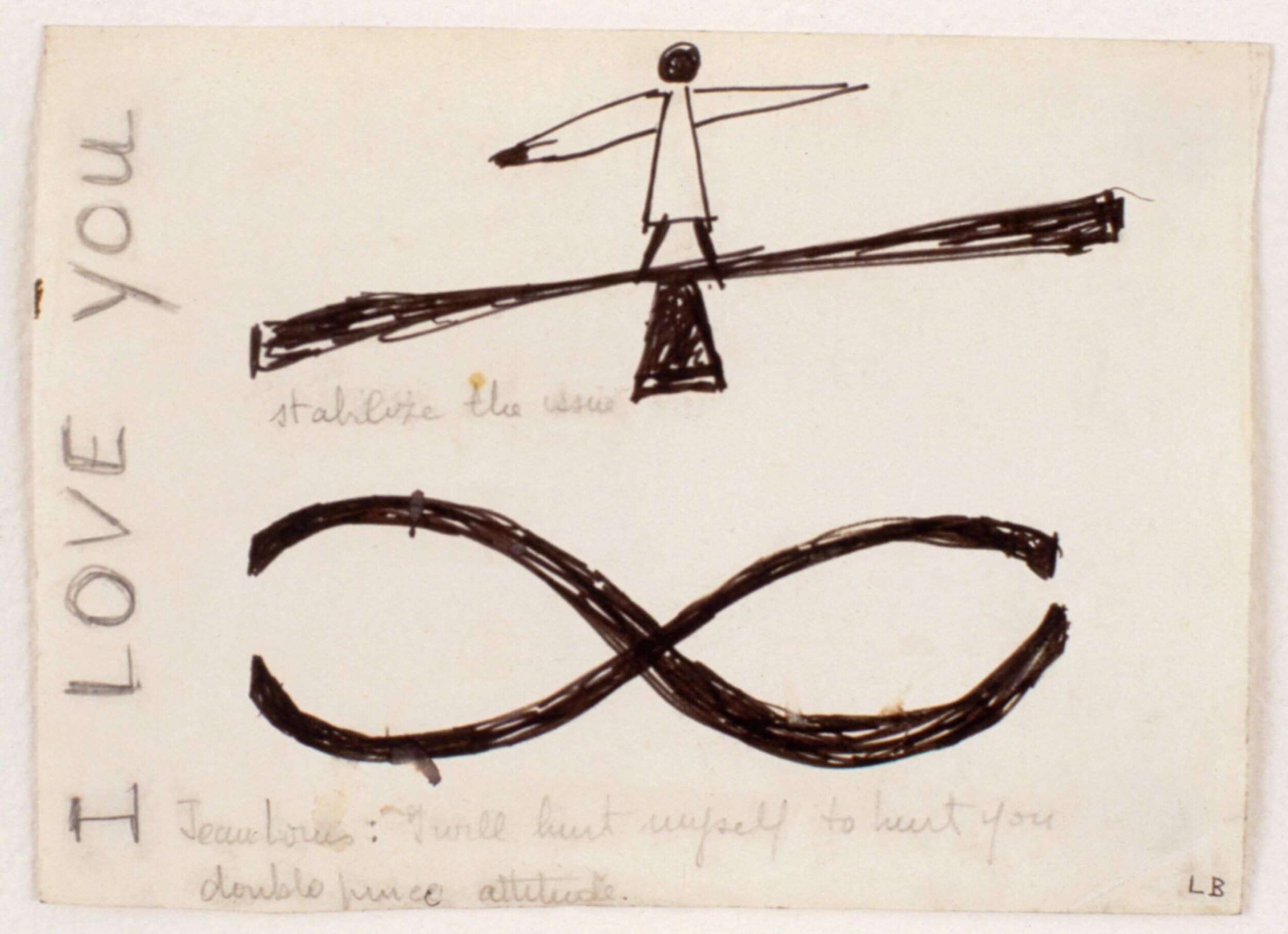

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 1960. Image courtesy of Hauser & Wirth

Unlike the ambitious toil that the artist undertook on her larger three-dimensional creations, Bourgeois drew (and wrote) every day and so in their modest way the 14 pieces on show here can offer us a nourishing overview of some of her persistent themes and ways of thinking. Family psychodrama, for example, abounds in Untitled (1960), which features a figure with arms outstretched balancing atop a seesaw and underneath it the infinity symbol, tellingly ruptured at either end. Bourgeois’ accompanying handwritten text reads: ‘I LOVE YOU’ / ‘Stabilize the issue’ / ‘Jean Louis: I will hurt myself to hurt you. Double price attitude’. Jean Louis is her son and the combination of difficult balance and emotional martyrdom is redolent of Bourgeois’ always-complex relationship with the maternal role.

Elsewhere, in the first of two works labelled Untitled (both 1970), Bourgeois’ subtly iconic spiral motifs make their appearance. Spirals whirled throughout her sculpture and printmaking, and this procursive drawing itself might have been one of her insomniac outpourings or could have easily ended up as a compelling scrawl on the walls of her Chelsea townhouse – that enticing space that became an almost claustrophobic vortex devoted entirely to her creativity after the death of her husband in 1973. The second piece labelled Untitled seems to abstract bodily contours and landforms into corresponding shapes so that hillocks might also be buttocks and the red light of a sunset that creeps through the crevices of land might also be blood. The accompanying quote from Bourgeois, displayed beneath the image, explains that ‘it seems rather evident to me that our own body is a figuration that appears in mother earth.’

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 1970. Pencil and ink on paper. Image courtesy of Hauser & Wirth

Henriette (1986) is an ink and gouache study in the artist’s favoured red hue, showing a stylised leg with ball-and-socket knee joint. This same image of a false leg will later emerge as a more fully realised work, also titled Henriette (1998), in which a suspended wooden leg casts its shadow against a pastel pink wall. Pink is an affectionate colour for Bourgeois. Henriette was the name of her sister who suffered from a painful leg condition. The disembodied image of this leg somehow operates as a gesture that’s both loving yet coldly reductive. There are 12 years between these two Henriettes (and there may have been other studies in between), indicative of Bourgeois’ long creative vision and patience, and the fact that nothing was submerged in her subconscious forever. Everything would bubble to the surface eventually, in one form or another, often in what her friend, the writer Gary Indiana, imaginatively described as ‘libidinal spillage and reverberating trauma.’

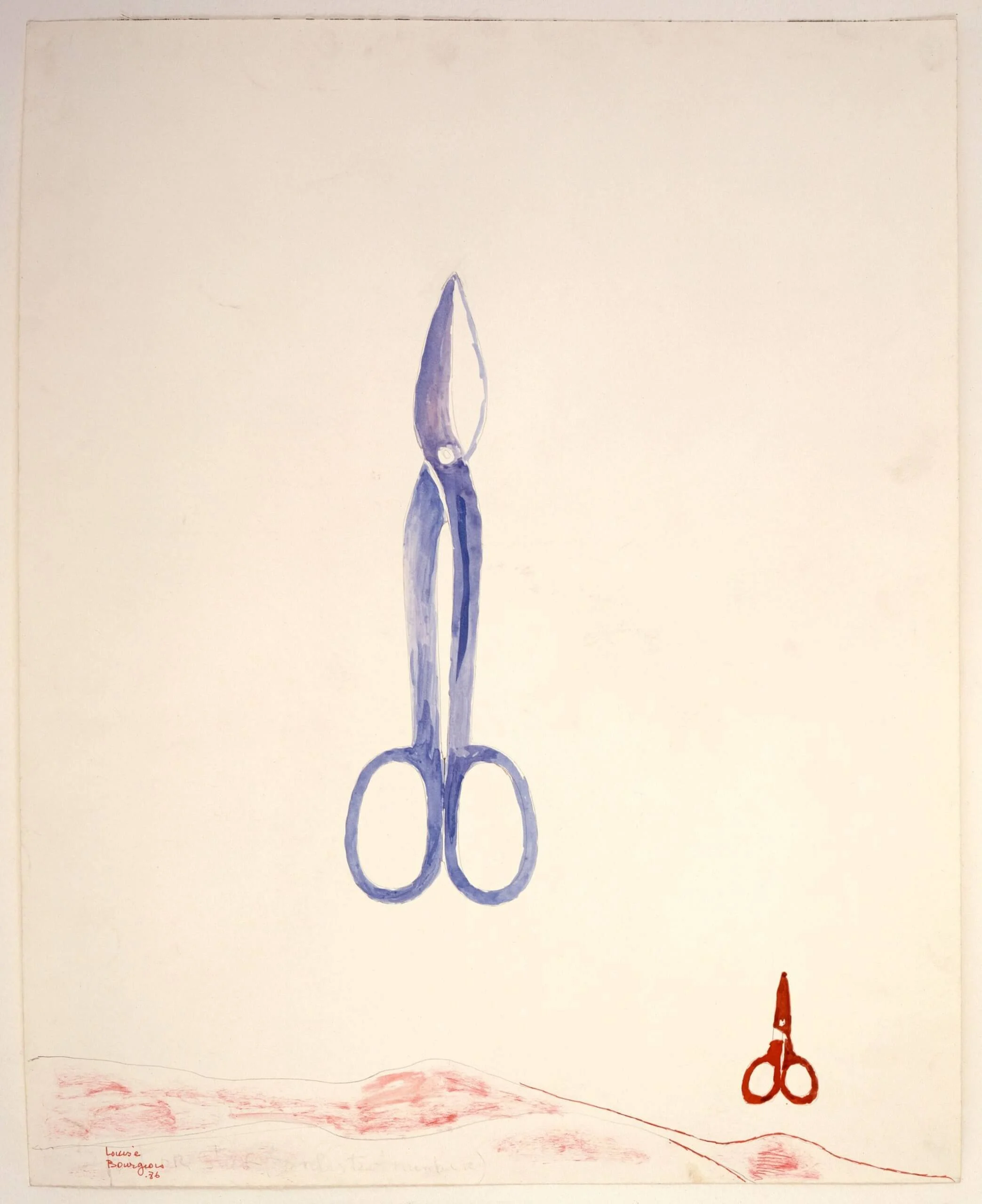

Returning to the maternal, Spit or Star (1986) imagines Bourgeois and her mother as pairs of fabric shears suspended side by side. Her mother had died when the artist was only 21 – a loss that she explored but could never expunge in her work. Bourgeois writes:

The large pair of shears is my mother. To me, my mother was very very big. My trust in her was complete. All I wanted was to be like her. But I am a little shears, a tiny one, though in just the same shape—the same everything, and I was pleased with that. That she was a monstrous cutting instrument didn’t matter to me. I liked her the way she was: very dangerous.

Louise Bourgeois, Spit or Star, 1986. Image courtesy of Hauser & Wirth

How rare it still is for women to be represented by the tools of their trade and not their relation to a male social order. How rare for artists from the great age of psychiatry to actively honour mothers and not revile them. Bourgeois offers us both; the tools of two artists, two makers, two women. One is made in the other’s image, though never quite equivalent. It is a gesture of symbolic obeisance, and also one of love and respect. In its simple scope of feeling, it is this piece within the exhibition that seems to most closely exemplify Bourgeois’ own description of her creative method:

It is not an image I am seeking. It’s not an idea. It is an emotion you want to recreate, an emotion of wanting, of giving, and of destroying.

Not all of the drawings exhibited here have an aesthetic appeal in and of themselves. Sometimes they are baffling, sometimes thin, even forgettable, but at the very least they all provide a snapshot of a very distinct artistic oeuvre. They are imbued with the power and intrigue that comes not just from the artist’s hand but from their proximity to her powerful persona and mind, and her extraordinary life. At some stage between the fourth and fifth of the chronological images, Bourgeois becomes involved with the American Abstract Artists Group and also befriends an older generation of artists including Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. She configures herself more fully as an artist. She moves into the house on West 20th Street where she will live out the rest of her life. This is what she is doing when she is not at her desk making these images. This sense of an artist’s life occurring beyond the page would no doubt be magnified by seeing these works in the flesh, with their creases and smudges and the infinitesimal signs of ageing that a simple screen JPEG cannot fully convey. These drawings are also relics of time, place and experience. They are missives from the liminal spaces of a brilliant mind; postcards from the wonderful, awful bedlam of the past.

***

A note on exhibiting. In the midst of the current coronavirus pandemic, much of our cultural life has moved online. Many large institutions are sharing previously unseen digitised versions of their collections, while numerous individual practitioners and smaller organisations are busily devising ingenious ways to make work, share and connect via the internet. Writer Orit Gat recently asserted in an article for Art Agenda that ‘giving a title to a group of JPEGs does not an exhibition make.’ Hauser & Wirth’s ‘inaugural online exhibition’ is simply that, alas. The supporting linked articles are interesting, the aesthetics of the site are fine, but the boast that the images are being brought ‘directly to your screen’ reads like a throwback to the days of dial-up and AOL. Nothing about the collection is like an exhibition. There is no way to navigate smoothly between pieces, only endless returns to the homepage – the virtual equivalent of traipsing back to the museum foyer before you are allowed to enter the next room. There is no sense of relative scale and not much consistency in the selected Bourgeois quotes; some are relevant to the piece they accompany, some are not even from the same era.

Another aspect of lockdown life is that we are taking culture into our own hands, so I decided to do this myself for the Bourgeois exhibition. Bourgeois was a mistress of scale, not necessarily through representations or embodiments that were simply ‘too large’ or ‘too small’, but scales that are also somehow uncanny or unnerving in their relation to us. I decided to go large and immerse myself physically into projections of these drawings. It was extremely pleasurable. Here I am, immersed, directly to your screen.