Sunil Gupta: From Here to Eternity at The Photographers’ Gallery

Sara Jaspan

Sunil Gupta, Untitled #13, 2008. From the series The New Pre-Raphaelites. Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, Stephen Bulger Gallery and Vadehra Art Gallery © Sunil Gupta. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2020

Sara Jaspan reviews Sunil Gupta’s first major UK retrospective, ‘From Here to Eternity’, at The Photographers’ Gallery in London. The exhibition is co-curated by Mark Sealy, director of Autograph ABP, and accompanied by the release of a new photobook of Gupta’s work. ‘From Here to Eternity’ is scheduled to run until 24 January 2021 and will then travel to the Ryerson Image Centre in Toronto in autumn 2021.

The headline image of Sunil Gupta’s first major UK retrospective at The Photographers’ Gallery in London is a deeply powerful one. It forms part of The New Pre-Raphaelites (2008) – a series of ten photographs he created to support the growing battle against Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, commonly referred to as the ‘Anti-Sodomy Law’. Introduced during the British colonial era, the legislation criminalised ‘carnal intercourse against the order of nature’ and was used as a legal pretext for the systematic oppression of the country’s LGBTQIA+ community. It was not overturned until 2018.

In creating the series, Gupta worked with consenting models who were legally prohibited from expressing their genuine sexual orientation or gender identity under Section 377. Each theatrically staged photograph recreates a scene from a famous Pre-Raphaelite painting through poses, sumptuous costumes and richly coloured backdrops. The art historical reference plays upon the Brotherhood’s central tenet of ‘truth to nature’ by seeking to convey the sitters’ ‘natural truth’ or authentic selves. It also creates a visual link back to a period during the height of the British empire, when India was under colonial rule, and inserts the queer, non-white body into a Western Imperialist tradition that has largely denied its very existence.

You don’t need any of this information to be affected by the image, however. Its primary power lies in the model’s piercing gaze. They seem to stare directly down the barrel of the camera into your soul; demanding to be seen and recognised on a very basic, human level. Once you’ve locked eyes, it’s difficult to look away.

The series sought to visualise a modern Indian queer identity that is still being formed after years of repression and ongoing prejudice. Moving through the exhibition, this theme of creating visibility (explored in unison with the complexities surrounding representation) emerges as central to Gupta’s ongoing career as an artist, activist and campaigner. Viewed as a whole, ‘From Here to Eternity’ tells the very specific story of his own life, and with this, the lives and marginalised experiences of so many others too.

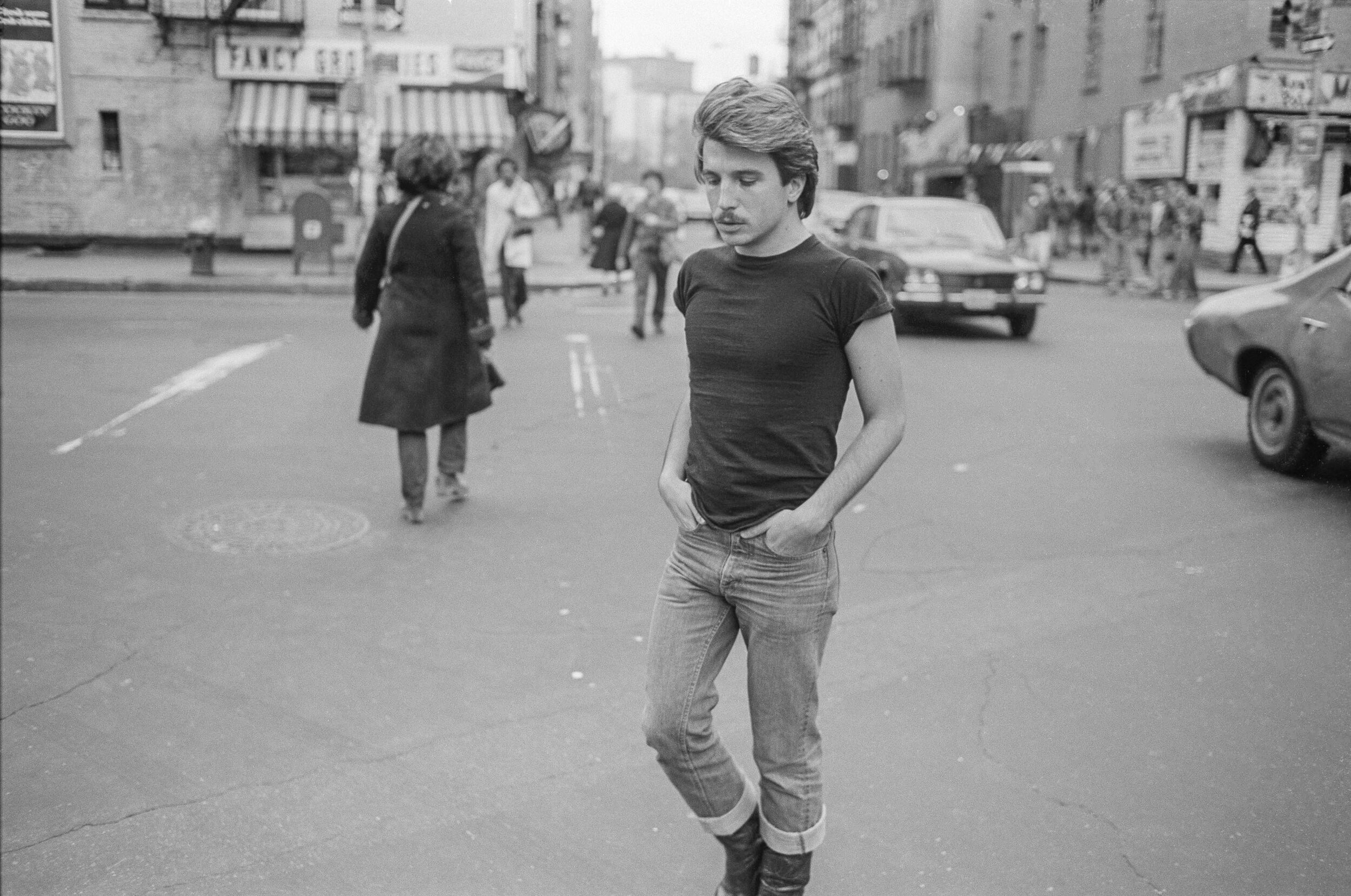

Spread across two floors, the chronological hang begins with an intimate, previously un-exhibited series of early photographs that document Gupta and his family’s emigration from India to Canada as a teenager in 1969, followed by his ‘coming out’ and formation of an extended gay family in Montréal. He later moved to New York, studied under the eminent street photographer Lisette Model, and became active in the city’s Gay Liberation Movement. Presented in one long horizontal strip, like a street, the 60 black and white documentary style images that make up his first formalised series, Christopher Street (1976), capture ‘the heady days after Stonewall and before AIDS’ (Gupta). He spent his weekends cruising the West Village with his camera, taking photographs that brim with a brazen sense of desire and easeful openness that remains absent from the rest of the exhibition.

Sunil Gupta, Untitled #22, 1976. From the series Christopher Street. Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, Stephen Bulger Gallery and Vadehra Art Gallery © Sunil Gupta. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2020

After following his lover at the time to London, Gupta was shocked to encounter what he later described as the ‘Paki-bashing’, homophobic climate of Britain in the late 70s and 80s. He had hoped to repeat Christopher Street around the areas of Earl’s Court, King’s Road and the West End, but found this almost impossible: ‘Even what appeared to be a concentration of gay life was not dense enough to create its own public space’ (Gupta). Instead, London (1982) ended up focusing on whosoever caught his eye: ‘migrants, people of colour, gay men, elderly people out and about on their own’. The energy could not be more different; strikingly guarded and inward.

It is from this early point in his prolific career that Gupta’s practice noticeably shifted – away from simple observation, toward photography as an activist tool for creating visual and cultural space for those that have been denied it.

A powerful example can be seen in his series “Pretended” Family Relationships (1988), where issues of race, representation and queer culture combine. The work is made up of portraits of multi-racial gay and lesbian couples together in their homes or in public, presented alongside reportage-style photographs from a demonstration against Margaret Thatcher’s notorious Clause 28. Passed in 1988, the legislation banned positive representations of same-sex relationships and the teaching of homosexuality as acceptable within schools, labelling it a ‘pretended family relationship’.

Despite the shift in time and cultural context, the work chimes with many of the themes in The New Pre-Raphaelites – the sense of love and natural intimacy between the couples directly contradicting the implied notion of ‘unnaturalness’, and photography again serving as a political weapon against the erasure of queer culture. The series equally forms another instance of Gupta’s efforts to represent queer people and multi-racial relationships within the longstanding tropes of dominant visual culture – in this case, the ‘traditional’ family portrait.

Presented nearby, two images from Memorials (1999) serve as a poignant reminder of how deep and violent the homophobic sentiment still was within Britain and America around the time.

Sunil Gupta, India Gate, 1987. From the series Exiles. Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, Stephen Bulger Gallery and Vadehra Art Gallery © Sunil Gupta. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2020

At the centre of his work, Gupta points to the ever-present question: ‘What does it mean to be a gay Indian man?’ From the early 1980s on, he made numerous trips back to India motivated by a personal desire to understand the hidden realities of life for gay men there, and to use photography as a way of both testifying to its existence and highlighting the invisibility of this socially and politically oppressed group. Sensitive to the ethical complications surrounding this, it was on the streets of his hometown Delhi that he developed his method of ‘staged documentary’, photographing only people who agreed to take part and working with them to construct what appeared like documentary pictures of the sites where queer men typically met.

The resulting series Exiles (1986-87) forms a polar opposite to the freely roaming game of looking and being seen in Christopher Street, with the majority of the men keep their back to the camera or their head out of shot. Anonymous quotes accompany each image, reflecting the vast spectrum of damage and pain caused by the closeting of a community. One man speaks of his longing for love rather than the ‘party and park scene’, another of the pressures to get married within a heteronormative society, another still of their distrust for Americans who come over ‘talking about AIDS and distributing condoms. Nobody believes them.’

Sunil Gupta, Manpreet from the series Mr Malhotra’s Party, 2011 Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, Stephen Bulger Gallery and Vadehra Art Gallery © Sunil Gupta. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2020

Made 20 years later with a group of young LGBTQIA+ activists and students in Delhi, Mr Malhotra’s Party (2006 – ongoing) reflects a very different situation. One in which, whilst still legally repressed, people were growing in confidence – enough to not only face the camera, but boldly, with what reads like a defiant sense of pride. In a recent online talk for Somerset House, Gupta describes how public parks had largely been replaced with meeting online, yet he was keen to locate his subjects ‘geographically in the heart of the city – there in everyday life. I wanted to say visually that these are your sons and daughters, brothers and cousins. They’re not anybody different. They live right here with you.’ Adding: ‘in the absence of knowledge people create monstrous identities.’

Resonating with these words, From Here to Eternity (1999, after which the exhibition is named) responds to Gupta’s diagnosis of HIV a few years earlier, during a time when queer people were being demonised within mainstream British media as monstrous carriers of the ‘gay plague’ and branded by the state as irresponsible. The series of six diptychs presents a tender riposte to this dehumanising narrative, each one combining an intimate self-portrait of Gupta receiving hospital treatment or alone at home, with the daytime façades of nearby sex clubs. Shuttered and naturally lit, these sites lose a lot of their charge in the same way that Gupta’s fragile and naked body is inscribed with an inherent sense of humanity that runs counter to the fear-fuelled public discourse.

Over the last 40 years, Gupta has not only sought to bring forbidden love and ways of being out of the shadows but also highlight issues of race and migration. Reflections on the Black Experience (1986) led to what the artist now considers to be the most important project he’s ever been involved in: the formation of Autograph ABP – an organisation dedicated to supporting photographers from racial minorities and confronting the lack of visual representation of marginalised groups in British society. Though progress has been made, his long-standing friend Mark Sealy – the director of Autograph and co-curator of ‘From Here to Eternity’ – describes the association’s battle for visibility as constant. With racism and homophobia still very much part of the fabric of society in Britain and around the world, Gupta’s long-overdue retrospective is a vital reminder of the need to keep fighting against this.

After all, to be truly seen is to be recognised and accepted as a fellow human; defusing the forms of othering and negation that otherwise occur. Gupta’s activism is guided by his understanding of this and the importance of seeing others like yourself represented. Let’s hope the legacy of his work lives on.

Sunil Gupta: From Here to Eternity is on show at The Photographers’ Gallery until 24 January 2021.