This Land is Our Land: Interview With the Curators

Sara Jaspan

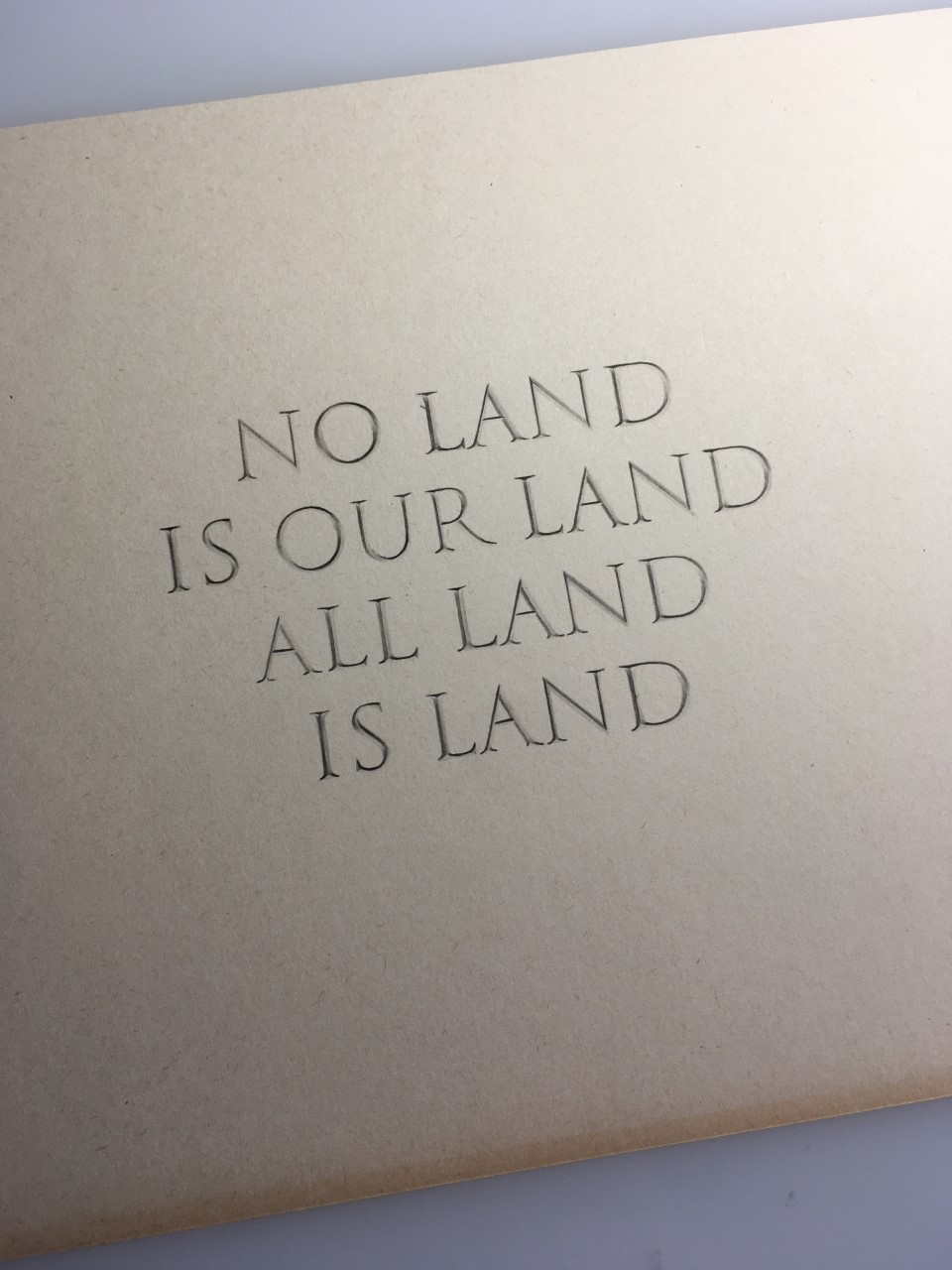

Lisa Wilkens, No Land Is Our Land All Land Is Land (2019). Chinese ink on paper

On the 29th of March 2019, the day of Britain’s scheduled departure from the European Union, a group of artists set out on an anti-Brexit walk in the Peak District National Park. Their route retraced that of the famous Kinder Scout mass trespass of 1932 – a civic protest that challenged the lines of private ownership that divided the countryside and curtailed walkers’ right to roam. The historic context provided fertile soil for a wider conversation initiated on a windy Derbyshire hilltop a few years earlier by long-time friends, artistic collaborators and organisers of the event, Simon Woolham and Stephen Walter, concerning issues of land, place, borders and freedom of movement.

‘This Land is Our Land’ at PAPER is an exhibition curated by Woolham and Walter that features work made by artists in response to the memory of the walk and the exchanges that took place along the way. Ahead of its opening, Sara Jaspan spoke to both curators to gain a deeper understanding of the ideas behind the project.

Sara Jaspan: Could you begin by explaining how ‘This Land Is Our Land’ first came about?

Simon Woolham: I suppose it all started about two years ago when Stephen and I met at the top of Axe Edge in the Peak District.

Stephen Walter: I’d come up from London with some friends and we were staying in a cottage for the weekend. I rang Simon on the off chance and said I’m nearby, did he fancy a walk? We were up there for two or three hours; discussing politics, the ridiculous fiasco of this ongoing Brexit drama, and questions around borders, common land and open access. What is shared? What isn’t? How much should space be regulated? All of these are recurrent themes in both of our practices and issues which we feel very strongly about.

SiW: Probably because of where we were, the conversation naturally led us to start pondering the famous mass trespass of 1932.*

StW: People don’t gather like that so much anymore – in protest or even just for the sake of gathering. We live in an age of individualism and quite selfish politics when old traditions are breaking down and less attention is paid to the communal good. Looking back, our meeting on Axe Edge felt something like a call to arms, and from the conversations that followed we decided to begin a project that would invite other artists to join us – to gather together, to talk about our common land and values, and to make work in response. We didn’t know what we would do exactly, but the act of gathering and pilgrimage were what seemed most important.

John Angus, Our Land / Warning - Freeman’s Wood (2019). Screen print on paper

SJ: A pilgrimage is usually a journey or a search for something. Why the notion of pilgrimage?

SiW: I think pilgrimage plays an important part in both mine and Stephen’s practice. I often make work by walking the edges of cities and towns or the realms between countryside and the built environment. It offers a way of thinking about space in very specific historic and current terms.

But, for me, pilgrimage is equally about conversation. It takes a lot of energy to do a group walk like the one we ended up taking around Kinder, as well as a willingness and commitment to be open with each other over the course of its duration. I think people have got more into the idea of walking alone these days, whereas I’m always keen for others to join in with the journey, and to engage and impart knowledge in whatever form. To open up streams of conversation.

SJ: What led to the decision to frame the project within the context of the Kinder trespass?

SiW: It was about a year after that initial meeting on Axe Edge and following lots of talks between me and Stephen that the idea of retracing the route came about. Our walk was never intended as a direct homage or re-enactment, however. The famous Kinder trespass served more as a memory or narrative. It was the element of mass process and protest that we were most interested in.

Saying that, the 1932 uprising occurred at a time of great political unrest, and by deciding to stage the 2019 walk as an anti-Brexit march, we were also trying to highlight these issues of space and land ownership within the wider political context of today, in the same way that the original trespass did.

StW: The Brexit argument offered an opportunity to re-evaluate what place means for us today, both as individual citizens and as a society. Do ideas now form place, or the other way around?

SiW: At its heart, however, the walk mostly provided the opportunity for a gathering of conviviality and a springboard or ‘collective reference point’ for the exhibition at PAPER that everyone is now making their own individual and collaborative pieces for. Not all of the artists that we invited were able to come but that wasn’t necessarily a problem. Those who couldn’t were simply kept up to date with how it went and the activity surrounding it.

SJ: Could you describe the day?

StW: A group of about eight of us set out from Bowden Bridge car park in Hayfield on the 29th March. We’d shared a public invite on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter welcoming anyone to join us, and Simon invited a number of artists whose practice specifically related to land and place. People gave small performances, took photos, made drawings and artworks, and gathered bits of material and information along the six-hour route.

SiW: I always had the idea of taking my artistic persona, the Oily Frog**, and spoke this mantra in character through my ‘shitascope’ (a toilet sewage pan connector) every hour on the hour.

And the oil spilled all over this land

It made glue out of the sand

Boiled the Irwell birds

till they were sticky and grand

The ants worked hard

to cut out what they can

We are the new Bell-Vue

Underneath and above you

Below the street and on top

The oil filled us all up

(Ruby Tingle)

It felt like I was singing to the land rather than to the people around us.

I also collected paper-based rubbings during the periods when I was back to being Simon. I see these as a kind of direct way of recording the landscape and am working them into a piece that traces the memory of the walk, in a similar way to how the walk was itself a memory of the 1932 trespass.

Simon Woolham, The Battle (2019). Kinder Scout rubbing on paper

StW: Artist Calum F Kerr decided to adopt a persona too and came as Aaron Ashfield (1731-1835) – a Hayfield-born British soldier who fought against the American revolutionaries and survived the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775. After he returned home, Ashfield is said to have roamed the Dark Peak regularly attempting to commune with the mermaid at Mermaid’s Pool, who he believed had the power to bestow immortality*** (he eventually lived to 104). Kerr conducted a questionnaire with other walkers that we passed, which related to the pool and what people knew about the folklore of the local area, whilst simultaneously playing upon the political absurdity of our age. The questions included things like: Are mermaids male, female or transgender? What colour are they? Do they migrate? What’s their view on immigration?

I collected an earth sample from the summit of Kinder Scout and – along with Calum and Reece Jones, a ‘Chaucerian trio’/artist initiative that we formed under the name TRESPASS – carried it all the way from to Market Gallery in Huddersfield via the Pennine Way; a journey that took another two days to complete. The jar of soil will be presented as a sacred offering as part of ‘INTER-SECTION’ – a concurrent group exhibition that Simon is curating alongside ‘This Land Is Our Land’ at PAPER that will focus on artist-led initiatives that respond to politics of space and place-specificity. There was of course an element of the absurd in this act too, which chimed with the wider project – inviting people to join us on some sort of group pilgrimage without allowing a culture to have percolated around it first.

Simon Woolham as the Oily Frog (left) and Calum F Kerr decided to adopt a persona too and came as Aaron Ashfield (right)

SJ: Did members of the public engage with what you were doing?

SiW: They did, especially with those of us in costume. (Lots of walkers wanted their photo taken with the Oily Frog!) And we heard plenty of comments like; ‘This is an anti-Brexit protest, isn’t it?’, probably because it was on people’s minds.

StW: I guess you say hello to everyone up there anyway. That’s what happens when you go for a walk somewhere like Kinder – people want to stop and chat, partly because it’s an excuse to rest! There was a very jovial atmosphere.

SJ: And how will the project translate into the exhibition at PAPER?

SiW: The artists are all going to send us their work and it will be presented like a ‘sporing’ wall of ideas, notes, drawings, and paper ephemera. The exhibition isn’t intended to come across as something finished; more a growing, evolving series of thoughts and reflections.

StW: We were keen to avoid giving the artists a solid ‘brief’. The project offers the freedom to respond in whatever way chosen, and so may not produce something very succinct or cogent in its message. It will probably highlight certain patterns and recognisable links between different artists and their overlapping interests around place, but I imagine it may equally create the impression of ideas breaking down – more so than we’re perhaps comfortable with.

SJ: And the title?

SiW: It’s borrowed from the writer and campaigner Marion Shoard’s landmark book This Land is Our Land: Struggle for Britain's Countryside (1987), which examined the extent of the power that landowners held in Britain and the history of the struggle over land rights in the UK and around the world. Of course, it also riffs off the 1945 American folk song by Woody Guthrie. It’s interesting that the song has been used in many different ways over the years, for example as an anthem for nationalism as well as peace and union. Shoard’s emphasis of ‘our’ is like a reclaiming, in a sense. And it perfectly encapsulates our anti-Brexit sentiment – that we need to overcome barriers between people rather than enforcing more, and to respect this Earth as a collective land for all people to move through as they wish.

‘This Land Is Our Land’ runs at PAPER in Manchester and ‘INTER-SECTION’ at Market Gallery in Huddersfield both run until 3 August.

* The mass trespass of Kinder Scout on 24 April 1932 was a notable act of wilful trespass by a group of around 400 ramblers. It was undertaken to highlight the fact that walkers in England and Wales were denied access to areas of open country; and marked the beginning of a campaign that eventually culminated in the Countryside and Rights of Way (CROW) Act 2000, which legislates rights to walk on mapped access land.]

** The Oily Frog originally began as the Gentleman Frog and came into being through my performative collaborations with artist Ruby Tingle. He changes and adapts depending on his environment and was the Pale Frog (paper-like) the night before the walk for a performance at Chetham's Library as part of Not Quite Light – a festival that explores histories and textures of the city. The Oily Frog crept out of the polluted River Irwell in search of the river’s source and wears its environment and heart on its sleeves.

*** Mermaid’s Pool is a shallow moorland tarn on Kinder Scout. According to legend, it is inhabited by a beautiful mermaid who, if spotted on Easter Eve, will bestow the gift of immortality.