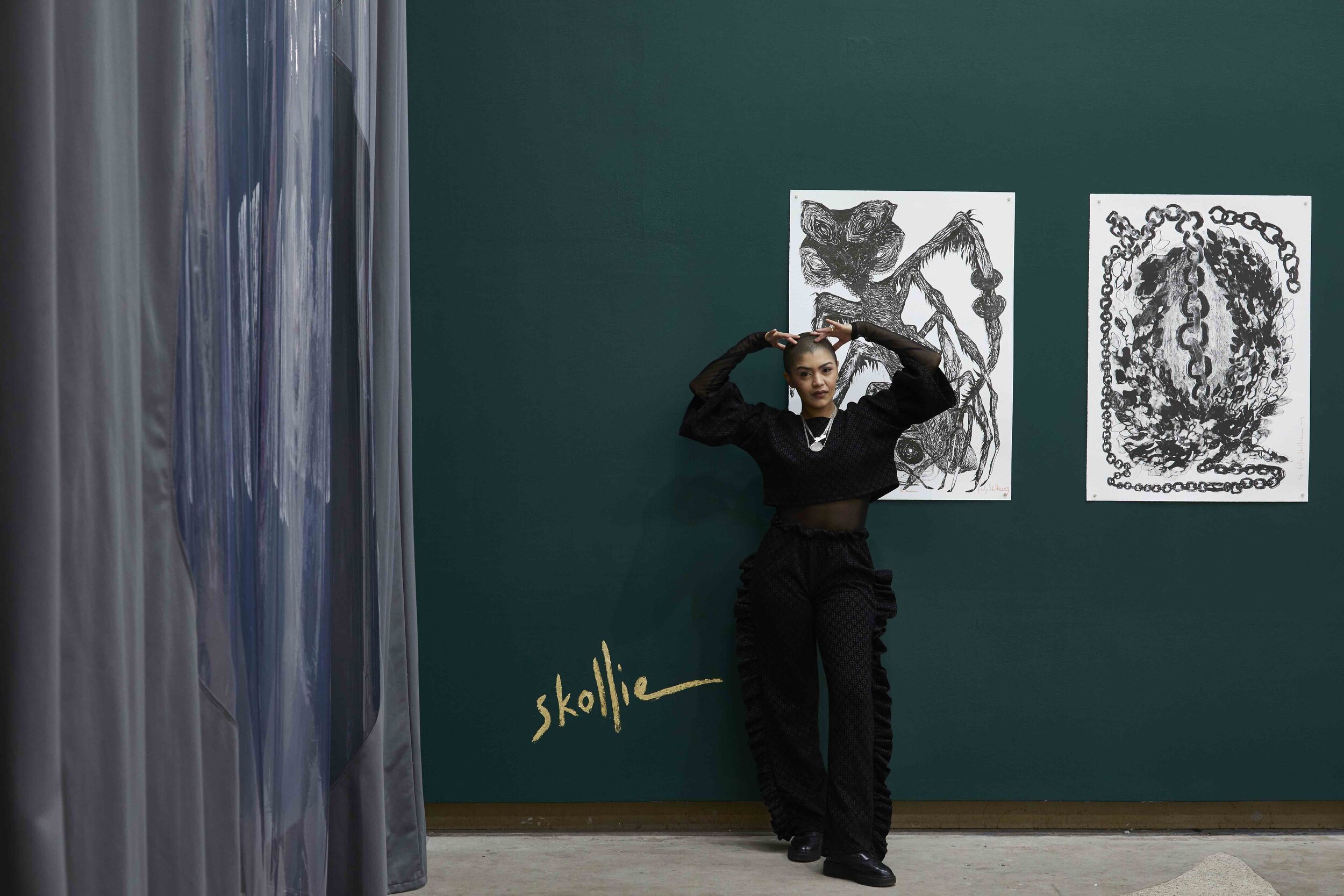

Lady Skollie: Weakest Link at Eastside Projects, Birmingham

Greg Thorpe

Photo by Stuart Whipps, courtesy of Eastside Projects

‘Weakest Link’ is a solo exhibition by South African artist Lady Skollie, presented at Eastside Projects Birmingham until 14 December. The 13 works on display include litho print, collage, acrylic paint, crayon and mixed media on paper. All of the following quotations are by Lady Skollie and were recorded by the author at the gallery in October 2019.

“My culture is born from rape,” Lady Skollie tells the audience during a talk at Birmingham’s Eastside Projects back in September. Then she laughs to fill our difficult silence.

“It’s okay,” she explains. “In South Africa we laugh before we cry.”

Lady Skollie is 32, originally from Cape Town, but based in Johannesburg. She is an artist who works primarily on paper but whose online presence, real-life conversation and performance can also be thought of as part of an expanded practice that altogether speaks to her proud and complex origins as a Coloured person of South Africa.

“Coloured people were the first people to be vanquished by the colonials.”

An understanding of the Coloured experience is key to fully engaging with Lady Skollie’s practice, and she is more than happy to teach. Learning about South Africa through the eyes of a young Coloured woman who is deeply connected to her ancestry will make you feel angry and bewildered. That’s fine, it’s intended. ‘Coloured’ is a multiracial ethnic identity and culture connected but not limited to the Khoisan. Read about it.

“Anger can unite people and that’s what I want my work to do. This is not Ubuntu.”

‘Ubuntu’ is the South African concept of gentleness, humanity and compassionate thinking.

‘Skollie’ is South African slang for a shady character, we might say a ne’er-do-well, a geezer, a sleeveen, a player, perhaps a scally. Racist whites would use the word to describe Black people who were deemed to be out and about when and where they ‘shouldn’t’ be.

Lady Skollie’s current exhibition at Eastside Projects in Birmingham is called ‘Weakest Link’.

Photo by Stuart Whipps, courtesy of Eastside Projects

“Sometimes all it takes for a chain of generational trauma to collapse is a ‘weak’ link.”

To Skollie, this collapse allows for an expression of that trauma, which covers generations, and therefore it is the artist who is the ‘weak link’ and who takes the responsibility of facing, processing, making, sharing.

Here, I’m attempting to mimic Skollie’s use of a linked chain through the form of my writing in order to honour her metaphor of connection, and to try to illustrate the exhilarating way her mind jumps between connected topics as I experienced during our conversation.

The chain of course is sometimes not a metaphor.

“The curator [of Eastside Projects] said to me, ‘Ah, I see you have been researching the history of chains in Birmingham.’ I had no idea what he was talking about so then of course I researched. The majority of the chains and ironwork used in the slave trade originated here in Birmingham.”

The resonance of an African woman coming to the place of the origin of such terrors is profound, and to try to signify some of that, each of the many paintings that fill the gallery walls are connected by a single painted chain.

During Skollie’s artist performance, which took place in October in the gallery space in front of her work, we were reminded of this part of the city’s history. Subsequent research indicates Birmingham was a strong supporter of the slave trade, signing pro-slavery agreements and so forth.

As audiences we must find ways to express gratitude for the teaching that artists of colour give to us in order that these truths can survive the literal and metaphorical whitewashing of history. Supporting the work of these artists is one way. This is particularly vital at this moment in time when people are growing ever more mindlessly nostalgic for the horrible cruelties of empire.

Lady Skollie does not mind about your discomfort, your inability to decolonise your mind, about your defensive racism. That is your work, not hers.

Photo by Stuart Whipps, courtesy of Eastside Projects

“I was in a store earlier and a woman asked where I was from. I told her and then she said, ‘Oh, your English is very good.’ So I replied, “Well, thank you … for colonising us!’”

For Lady Skollie, there are no coincidences, only fatefully informed decisions made with the assistance of ever-present ancestors. Decisions about earrings, friendships and art shows all have ancestral consideration. People in her culture possess what she calls a ‘genetic spirituality’. It’s inescapable.

The day that I meet Lady Skollie, I’m wearing a jumper that’s something close to racing green in colour. She points out that this is also the colour she has painted the gallery walls. The paint was concocted and mixed in collaboration with another artist.

In the gallery I am interested in the scale and layering of some of her pieces. They are lustrous. It seems as if they have been painted and crayoned over and over until they are saturated and almost sagging with colour.

“I have actually had curators waste my time and money trying to force me to paint on canvas, which I literally do not do. I think my work on canvas is ugly! They feel the work will valuate more on canvas, but it’s not the same work. I work on archival paper.”

This seems a good moment for me to explain the origins of the name ‘Fourdrinier’ and the magazine’s remit for covering artists who are making work on paper.

“I love England,” she says. “There are so many dorks here!”

PAPSAK PROPAGANDA (2019) is a good example of Lady Skollie’s use of form, colour and incident. The palette is black and crimson, bloody and night-sky purple, rendered in acrylic and wax. The figures are two girls, their bodies fibrous and strong and entwined. Their faces are blank gold suns and their feet vanish into a vat of grapes. The context is to the point:

“As a child they took us to a wine farm,” writes Lady Skollie in the exhibition programme, “[to] step on grapes for hours; we had fun but now I realise we made some wine for THE MAN.”

In South Africa, a ‘papsak’ is a bag of wine and the work references the ‘dop system’, a practice from the 1830s onwards of paying exploited South African workers in alcohol instead of actual wages, only outlawed in 2002. Alcohol is an addictive coping mechanism for trauma and suffering. With this knowledge, the retraumatising possibilities of the grape-treading girls are soon apparent. Links. Connections. Chains.

“New chains are mental and learned.”

This work has travelled to Eastside Projects with Lady Skollie from a recent solo show in Cape Town. Her position as an artist back home seems to be simultaneously celebrated, marginal, infamous and unprecedented.

Example: Earlier this year, Lady Skollie was headhunted to produce artwork for the South African Mint, resulting in a piece of her work appearing on the R5 coin – something that she finds it hard to position the full significance of. Khoisan artwork, by a woman, on a coin, in general circulation, in South Africa. That is, artwork from the most marginalised segment of society passing from hand to hand in the general population. Lady Skollie is both proud and questioning about the achievement.

Photo by Stuart Whipps, courtesy of Eastside Projects

“Self-flagellation is such a Coloured thing.”

I wonder how a person can hold this trauma and the responsibility of it. How does one… cope?

“I’m too vain for drugs and alcohol. I’m light skinned; it shows. Sex and power are my drugs. But sex in South Africa is so messed up.”

She describes incidents, some personal to her and some well-known in South African media, that demonstrate the terrifying power that men hold over women in public and private spaces there.

Back to the exhibition, Lady Skollie talks about her consistency of tone and subject and commitment to her work. ‘Weakest Link’ is a great first encounter with the artist’s practice and vision:

“Consider this show ‘the Lady Skollie Care Package’ or a ‘Greatest Hits’ of sorts; a combination of my leitmotifs.”

How does her work find its audience back home?

“Apartheid has killed curiosity. People don’t have hobbies, except drinking. People don’t go out of their comfort zone to discover new things. Apartheid does that to you. People don’t feel comfortable going to galleries, because they weren’t previously allowed to. In my practice I am trying to make those places less scary for people. I’m a purist though. I’m trained in Fine Art. But also, I think the white cube is so lame.”

Diana Ferrus is a South African poet who wrote a well-known piece about Saartjie ‘Sarah’ Baartman, the Khoikhoi woman who was enslaved, had her name taken away from her, was rechristened the ‘Hottentot Venus’ and was exploited around the ‘freak show’ circuit of Europe from 1810 to 1815. After her death in France, Baartman’s remains continued to be exhibited, continuing the degradation of her body. The power of Ferrus’ ‘A Poem For Sarah Baartman’ (1978), which opens with the line: ‘I’ve come to take you home’, led to the eventual repatriation of Baartman’s body back to South Africa in 2002.

At Lady Skollie’s performance, she reads the poem to us and the chains between Europe and South Africa take on yet another powerful dimension.

“My sister said to me, ‘You never listen, that’s why you never paint anyone with ears!’”

That might be so, but it would be hard to find an artist more attuned to the world around her, and the world that came before her.