Esther Teichmann: On Sleeping and Drowning at Flowers Gallery, London

Alison Criddle

Untitled, 2019

And then the depths push against her, releasing her to the light above. Held firmly in the sea’s grasp, she bathes in the moon’s glow. (‘On Sleeping and Drowning’, Teichmann)

An ocean of hair, a full moon of breast, a slip of seaweed and a shell held up to the ear to listen; a visit Esther Teichmann’s current exhibition ‘On Sleeping and Drowning’ at Flowers Gallery in London is to take a dip into the liquid realms between euphoria and eclipse.

The London-based, German-born visual artist works with photography across still and moving installations to explore relationships between loss, desire and the imaginary through sensory encounter.

The upstairs section of the Kingsland Road space is transformed into a layered liquid montage of photographs, painted canvas backdrops, sound, scent and tangible objects. At once a cave, a riverbank and a diving pool, Teichmann has curated an immersive realm in which to enter and explore. Feelings and emotions bubble up as sound reverberates across the exhibition rooms. In this kingdom, a school of floating cyanotype sea plants juxtapose oil-slick, black leather seaweed whips draped over nude bodies. Huge painted photographic backdrops of caves and riverside trees sit behind a skeletal wooden boat with cloud-like sails occupying one part of the gallery.

Within ‘On Sleeping and Drowning’, the Styx and Eden collide. Entering off the busy roads of East London, visitors are gently led by Teichmann into the waters of her making; guided into a return to liquid origins and sensorial encounter. Her alternate world has one foot on land, whilst simultaneously up to its neck in desiring ethereality. The effect is at once haunting, destabilising and magnetic. The works, all untitled, move within womb-like spaces of beds, swamps, caves and grottoes. There is a sense of searching through mythology in attempt to return; a thematic thread like Ariadne’s that both draws the viewer in and onwards, whilst acting as a lifeline reminder of the reality in which the dream visions are created.

The photographic images – of clouds or waves – slip in and out of darkness, evoking a liquid space of night. Bodies are dressed in seaweed, cloaked in floor-length hair, and wrapped in fabrics the same colour as the rock of the caves in which they are posed. Faces are turned away, half glimpsed, or else eyes are closed in reverie. This aversion has the beguiling effect of drawing the wide-eyed viewer in closer still – of leaning into the transitional spaces of Teichmann’s making. Cloaked in dripping inks and bathed in subtle hues, the sensuous bodies she depicts remain always just outside of our grasp. There is a desire to reach out and trace their forms; to touch the long hair of the woman in the shell grotto, to feel the slippery texture of the seaweed across the body, to stroke the rough rock face of the cave walls. It’s as if Orpheus and Eurydice were to play out their fateful game of looking and longing alongside Hans Christian Andersen’s Little Mermaid; allure and trepidation being never too far apart from one another.

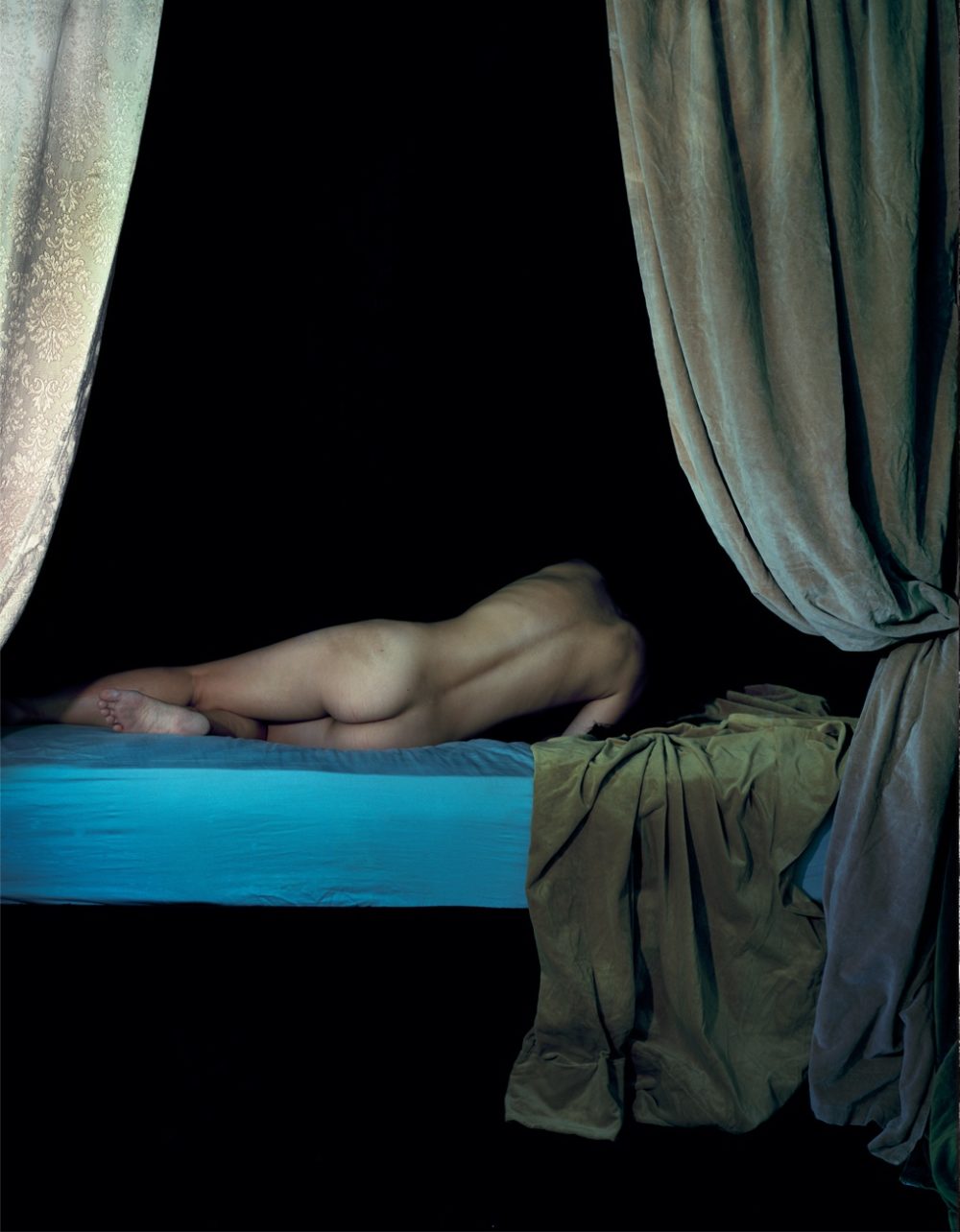

Untitled, 2019

Referencing the coral that is said to have been formed by Medusa’s blood spilled upon seaweed, Teichmann has the ability to transform one thing into another through her creative making and gift of storytelling that always leaves the right amount of space for the viewer’s own imagination to fill; allowing others to take the tales of her work into their own hands.

The works slide between autobiography and fiction. In one huge painted photograph, her parents row, reclining through an orange, purple and green back water, whilst the boat they sailed is anchored firmly in the gallery before them. ‘On Sleeping and Drowning’ form part of an ever-evolving that is expanded and re-configured in various ways – a series of myths, added to and extended with each re-telling.

Indeed, storytelling plays a central role in Teichmann’s practice. In Fulmine, (2015), a dark-haired female performance artist turns her naked body slowly, softly over an aquatic blue-sheeted mattress. Framed by velvet gold drapery, she is encircled in darkness under its canopy. Shot in real time, her slow movements become a mesmerising study of gesture and form. Over the course of the nine-minute looping video, silence is followed by an original string quartet score by London-based Irish composer Deirdre Gribbin.

Although “nothing is slowed down – all footage is real time” (Teichmann), the reel time of the piece seems to collapse and loop, space becoming narrowed by the hypnotic twists and turns of the woman’s body. Her hair falls in waves across her (dancer Sophia Wang’s) barely visible face; glimpses of lips and ears are all we are afforded.

Appearing like a scene from a Renaissance devotional painting, the richly coloured canopied bed sits inside a garden cabin in San Francisco, where Teichmann herself lived and slept for a short period. Her practice is tied closely to text and to life. She explains, “My work is always very closely autobiographical, whilst also fictionalising autobiography – so the stories are the starting point.” In previous presentations of Fulmine, a short story – Fractal Scars – by Teichmann has accompanied the film. In June 2014, a string quartet joined to present a live score before a screening of the work at the launch of her ‘Mondschwimmen’ series at Zephyr in Mannheim (Germany), and, most recently, at the closing night of an earlier presentation of ‘On Sleeping and Drowning’ at Galerie Les Filles du Calvaire, Paris in May 2019.

In Fractal Scars, fiction bathes in moving image and memories of San Francisco’s Bay Area waters. Moving from the city’s giant ‘World Famous Camera Obscura’ at Bay House to the canopy bed to her seaweed-filled bath, the protagonist ‘V’ (a name that echoes openings and the auto-erotic) is submerged and immersed in memory. Sound, touch, sight, taste and smell swell up in this short but full film piece, as the performer’s body fills up the space of the screen:

V keeps a thicker kind of seaweed in her bathtub, the brackish salty smell reaching her boat-bed when a breeze moves across the room. She keeps these washed-up branches of slippery leather, so as to bathe within their drowned mermaids’ embrace. Filling the bath with warm water, V lowers herself into their tentacles as he sleeps oblivious, a few feet away.

As is the sea beneath them, so is she: swelling, roaring. She tastes her saltiness in his mouth, the taste of the ocean, the sweet smell of swamps. Deep-sea diving, eyes open, swimming from luminous turquoise into dark blue towards almost black waters. Unafraid, she swims down, through ocean caves, under waterfalls, no longer needing to breathe. Past and with all the women who are a part of her. (Excerpt from Fractal Scars)

Untitled, from Fractal Scars, Salt Water and Tears, 2014. C-type print

At once sensory, sensual, sexual and maternal, Teichmann returns the viewer to both the lover and the mother through her dream weaving; presenting haunting bodies in beguiling spaces. Bed, cave, boat, all are places to enter into, to move through, and to be transported within. The images she presents are contradictory moulds and memories of complex projected fantasies of desire. In The Poetics of Space (1958), the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard devotes a chapter of his writing to shells. In it, he contends that “Everything about a creature that comes out of a shell is dialectical. And since it does not come out entirely the part that comes out contradicts the part that remains inside.” Teichmann’s work inhabits this ‘in-between’ space of emergence and enclosure; the moments between sleeping and waking, breathing and drowning.

The bruised legs of the performer nod to a slippage between reality unseen. One of Wang’s passions is rock climbing and her grubby feet trace a movement between bed and beyond as she stretches and turns slowly under the canopy. Always almost on the moment of emergence, her body, fleshy and made small within the dark ocean cave of the bed space, is that of a sea creature within its shell; the space just prised open enough to see what lies beyond. The bed, as a place of conception, of sleep, of birth and often of illness and death, becomes the ‘in-between’ space that bears witness to life’s journeys.

Moving between text and image, Teichmann further extends the experience of exploration and encounter. Viewer becomes listener becomes reader as the gallery-goer watches the work, hears the string quartet, and then carries a paper takeaway gift of hand-written text home with them.

A recurring motif in her exhibiting and presentation practice, Teichmann’s paper takeaways might come in the form of a bookmark, a booklet, a postcard or a catalogue. In the case of the Flowers show, it’s a just-smaller than A4 sheet that’s cloud-blue on one side and sun-dipped on the reverse. The text is another gift of storytelling that shares the same title as the exhibition itself. Neither an extension of nor separate from ‘On Sleeping and Drowning’, it is representative of both individual and shared encounter. The creative fiction, like the artwork, is a vessel for holding and a movement through the space of encounter. To read the tale aloud enacts a retelling of dreams; projecting visions onto the mind of the viewer.

Teichmann’s work has a resonance that disarms. A large conch shell, photographed and presented in black and white, perfectly sums up the powerfully emotive qualities at play across the show. Smooth folds and a dark opening sensually evoke the female form, whilst its jagged-toothed edges allude to a threat that has not yet been spoken. To hold it to the ear might be to listen into its secrets. In its centre, it holds the myth of the echo, while externally it offers the singularity of its form. The shell nods to the sea whilst tracing its history; having been washed up, picked up, selected and posed for the image. The photograph, a reproduction of the original, doubly nods to the echo that is held within the shell; exposed only through proximity to the listening, imaginative body. Open to imagination, surrendering to the current of thought and creativity at play, the viewer as listener can explore the show anew.

I retraced my steps around the gallery, following the form of the listening shell across the works – from the photographs of the grotto wall, covered floor-to-ceiling with shells; to the cloud images, echoing sea-foam and waves; to the conical curves of the ear of the woman with eyes closed in reverie, encircled in folds of hair and seaweed fronds. The smell of salt filled my sea-starved nostrils. The sound of the quartet washed out of the room where Fulmine twisted and turned. I folded the takeaway tale between my fingers. For the opening night of the exhibition, Teichmann presented the work not just with the live quartet performances but filled the air with specially selected scent too. In ‘On Sleeping and Drowning’, to see is to taste is to touch is to smell is to be held on the precipice between living and longing for a beyond. I stepped back out onto the stained pavement, my senses alight.

‘Esther Teichmann: On Sleeping and Drowning’ is on display at Flowers Gallery in London until 22 June 2019