The Art and Life of Dee Ridley: Part Three – Fenced Up

Jo Manby

Layla Curtis, Introducing ‘Trespass' (2019). Digital slideshow (detail)

In the third instalment of a series of creative texts by writer Jo Manby, her character Dee Ridley visits ‘This Land is Our Land’ at PAPER in Manchester. Read ‘Part One – Double Face’ here and ‘Part Two – Nettle Sting’ here.

Summer has come with the alternation of flash-floods and brilliant sunshine that used to mean spring; weather that signifies change.

It’s a damp Saturday and Tamsin and I have returned to PAPER to escape the rain and check out its latest exhibition, ‘This Land is Our Land’. Scanning the sprawl of photographs, maps, prints and drawings that crawl upwards from the base of the gallery walls, my eyes rest on a small watercolour. I can’t work out how the artist, Reece Jones, has managed to create the ghostly lettering that stands out so clearly from the flawless washes of paint, bearing the message: ‘Go Stay’, ‘Stay Go’.

Reece Jones, Go Stay - Stay Go IV (2019). Watercolour on conservation board, two panels

From the handout I learn that some of this material is ephemera gathered from an ‘anti-Brexit protest walk’ up Kinder Scout in the Peak District that the artists collectively undertook on 29 March 2019 – the day we were scheduled to leave the EU. The march simultaneously commemorated the famous mass trespass by ramblers in 1932 against the denial of access to roam the countryside. Three of the artists, describing themselves as a ‘Chaucerian trio’, continued all the way on from Kinder to Huddersfield carrying a jar of earth gathered from the plateau.

- It all sounds a bit mad to me, says Tamsin. But perhaps it was some sort of attempt to make sense of – or just reflect – the absurd political situation we’re all in at the moment.

- A form of anarchy, I suppose.

- A break out from the neo-liberal city.

Tamsin recognises one of the artists, Dale Holmes, a senior lecturer at her uni, and starts telling me about his ongoing research project, The New Aspidistra, in which he expands upon the art critic and anarchist Carl Einstein’s concept of the collapse of subject/object dualism through a range of mediums, including long distance endurance cycling. I’d not heard Einstein’s theory before, so it’s good to get the lowdown. For ‘This Land is Our Land’ and as part of The New Aspidistra project, Holmes cycled from the Emley Moor Mast near Huddersfield to the Berlin Fernsehturm TV mast in Germany last month – 3,000 kilometres in five days – taking a copy of his edited volume of The Graveside Orations of Carl Einstein (2019) to Rosa Luxemburg’s resting place.* My mum told me about Rosa Luxemburg when I was young, along with other radical women. A revolutionary socialist murdered for her politics a century ago, who, had she survived, could have changed the fate of Europe.

Our chat is interrupted by Camille calling me. I tell Tamsin I’ll take it in the gallery yard. She carries on looking at the work.

Camille’s drunk and upset.

- Hey now, I say. What’s to do?

- I need you here. As soon as you can. It’s Dad.

She doesn’t give much more detail. Back inside, I tell Tamsin I have to go to London.

- When will you be back?

- Tomorrow, hopefully. Camille’s in bits about something. Her dad Perry’s been up to his tricks again.

- I’ll hold you to that, says Tamsin, smiling. She looks at me through her fringe. Dee, there’s nothing going on between you and Camille, is there?

- There might have been once but there isn’t now.

Later I realise that probably didn’t sound too convincing.

Will offers to lend me his car. A 10-year-old battered Porsche. He can’t park. To sit down, I have to clear old takeaway cartons and drinks cans off the driver’s seat. The whole thing needs recycling. I’m not hanging around for a train (the northern section of HS2 isn’t yet a reality), so instead I phone Sixt and pick up a BMW from Piccadilly. I can indulge in some ‘accelerated psychogeography’ of my own, as Holmes puts it.

+

Graham Lister, Path(s) – Kinder Scout (2019). Oil on linseed treated paper

I head south on Chester Road to the M6. It’s a long drive and after a while I find my mind circling back to the exhibition Camille’s just pulled me away from. I can’t help noticing every piece of highway furniture – the signs, the cones, the barriers on the central reservation, the glittering black boxes that flash up warnings intermittently before collapsing back into sequinned darkness as you approach. Like Graham Lister (another of the artists who caught my eye back at PAPER), I start to feel more attuned to fences and barriers. The way parcels of land are partitioned off by utilitarian webs of plastic and nylon.

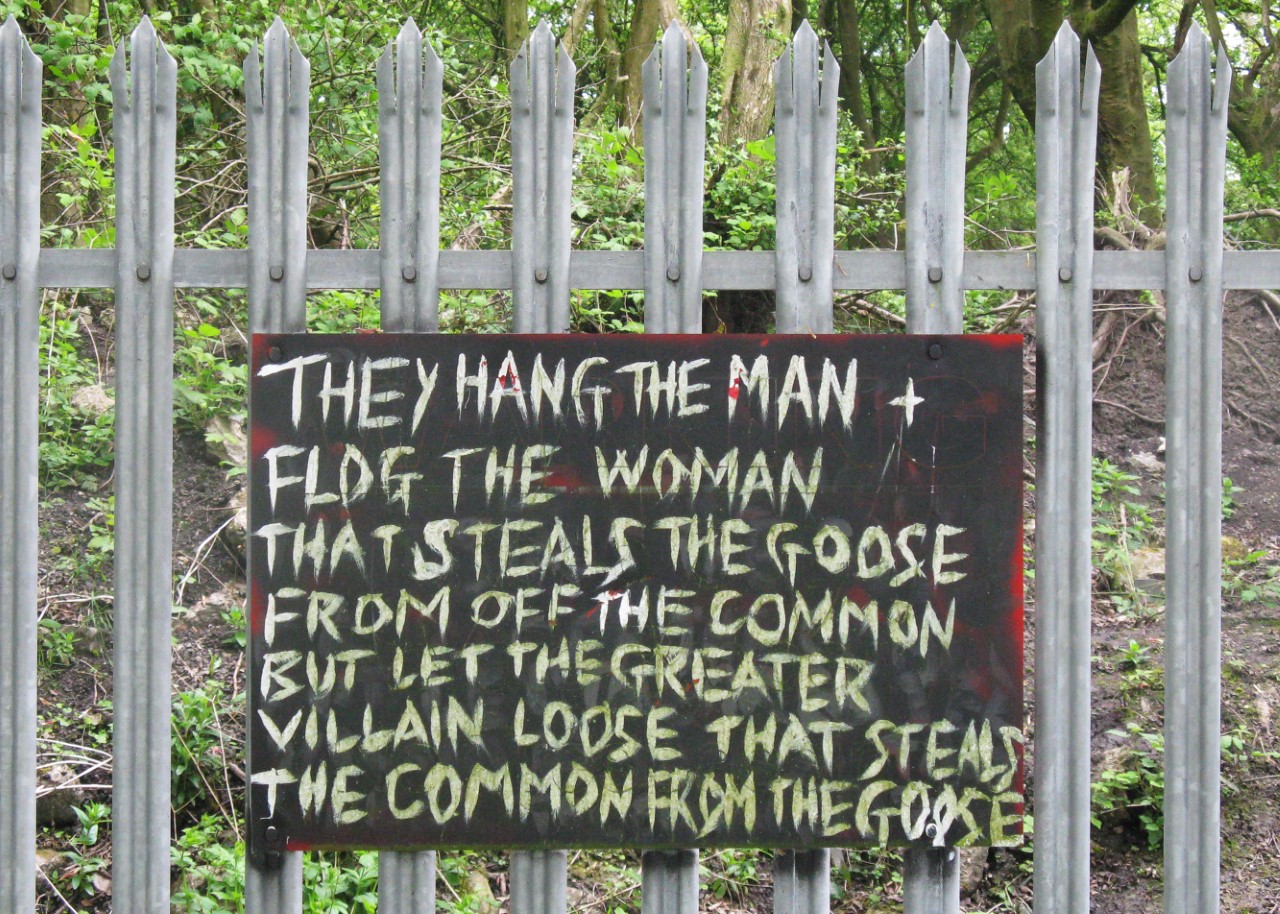

It occurs to me that the title ‘This Land is Our Land’ must have been borrowed from the environmentalist Marion Shoard’s landmark book from the 1980s. A copy had sat on my parents’ bookshelves for years and I’d dipped into it a few times. I was only a teenager back then and, although the ideas had seemed important, my 20s and 30s came around and life just seemed to take over. I remember the gist though; the division between the landed and landless in this country, the broken social contract whereby the legislation of post-war reformers has been eroded to weaken planning control in rural areas and promote subsidy for rural land use. Basically, these hedges and fences that flicker past as I drive, like the warp and weft of a thick green tapestry, make us all into trespassers. Lister’s works included watercolours from memory of the Kinder Scout walk, the trajectory they took depicted as a rich black earth path cutting through green rolling land.

When I stop at Frankley services, there’s a man resisting arrest in the food hall foyer. A group of primary age kids look on goggle-eyed, the teachers flapping like mother hens. Give them a couple of years and it will be business as usual. I check my phone; Tamsin’s texted.

- Seen any Oliver Easts on your travels?

- They’re everywhere, I message back.

I know Tamsin especially liked the show because it partly relates to her Archaeology MA. Re-readings of landscape. Contemporary artefacts uncovered in landfill and on the peripheries of towns and cities. By ‘Oliver Easts’ I assume she means the way he camouflages found detritus back into the generalised context of the street, the outskirts of Manchester and its industrial estates; lovingly painting old mattresses and discarded planks to match their surroundings.

Oliver East, Moss Lane East (2019). Vinyl paint and plastic paints

We were both drawn to the themes of civil resistance and temporary autonomy. Too often these days we find ourselves hemmed in by physical and virtual boundaries that are almost imperceptible yet impinge upon our freedom. Like the POPS – privately-owned public spaces – where cameras, security staff and other paraphernalia of the dystopian end-of-capitalism state confine and police our behaviour. Media City’s central plaza in Salford Quays, the Southbank on the Thames. As Foucault said, you become the principle of your own subjection; assuming responsibility for these power constraints without really realising you’re doing it.

+

I pay my way through the West Midlands toll and eventually roll through Brent Cross, Childs Hill and Fortune Green via a few roadworks. Shunt the car round Regents Park and leave it in the NCP at the back of Fitzroy Square. It’s taken me an hour to get here from Edgeware.

When I arrive at the apartment, Camille is still shaky. She hugs me tightly a moment then holds both my hands at arm’s length, looking me full in the face.

- What will I do if no one trusts me anymore?

- What happened exactly?

- Somehow word got out that Dad’s storage facility was raided, and they found evidence of forged provenance documents. People put two and two together and now three of my longstanding contacts have dropped me like a bloody hot brick.

I suppress a joke about Carl Andre’s pile of bricks at Tate being stolen goods. Equivalent VIII.

- It’ll blow over, I say, ineffectually.

- Yes, that’s what Dad said.

- You should maybe get away for a while though. Out of the smoke.

- You’re probably right. Plenty to do and see elsewhere. You will stay over, won’t you?

I know she needs to talk more about Perry, so I tell her I’ll head off in the morning.

+

The next day, we stroll down to VQ Bloomsbury on Great Russell Street. Sitting in the warmly lit, low-ceilinged café with its red wiring and caramel coloured banquettes, I pay the congestion charge on the TfL app while waiting for my steak and eggs. Camille will have nothing to do with steak, so she toys with a fruit salad and downs a hair of the dog.

- Some of his advice has led me to buy things I had no idea were illicit. Why would I suspect anything was wrong?

- It means you’ve got nothing to worry about.

- Apart from my reputation. He’s made me into a fence: I’m the legitimate front but I’ve been buying stolen goods. Not only that but I’ve sold some of them on too. I’m convinced he just wanted to generate decent paperwork.

Paperwork. We talk some more about Camille’s predicament, then I try to take her mind off it by asking if she’s been up to anything of interest lately.

- The usual lunches, the odd party. I saw a play last month at Camden People’s Theatre. Human Jam, it was called. She sips her very early cocktail. I was bored stiff.

- What was it about?

- Something to do with this archaeology company that supports big infrastructure projects – MOLA Headland, I think it was called? They’re invading London now as well as the countryside. Seems archaeology is a commerce in its own right these days.

- Sounds pretty interesting.

- It was alright. Did you know that 80% of the demolition required for HS2 is taking place in this very borough?

I say, no, I didn’t.

We chat some more but really there’s nothing much I can do. I reassure her I’ll be down again soon.

On the drive back, my mind slips away from Camille as the stern voice of the in-built GPS starts rattling out directions. Glancing back and forth between the small screen and the road, Layla Curtis’s maps open out in front of me, her practice concerned with their subjectivity and capacity to impose power. For ‘This Land is Our Land’, she chose to exhibit documentation of ‘Trespass’, an iPhone app which maps an oral history of Freeman’s Wood on the outskirts of Lancaster now fenced in by landowners. To gain access to the audio material, the app has to be used inside the perimeter of Freeman’s Wood, enticing the user to trespass.

Layla Curtis, Trespass (2015). App for iPhone

I’ve come across one of Curtis’s projects before: polar wandering (2005), a web-based line drawing generated using logged data from a personal GPS tracking device as she travelled through Madrid, Santiago, the Falkland Islands and remote islands in the Southern Ocean, headed for Antarctica. I start trying to visualise how Perry’s crisscrossing of the capital would look if it was GPS tracked. His dealings light up in my imagination like a new network on an old map of the world. He is like a node; a little LED pinpoint in a long, inter-linking chain, sliding along the trade routes that are as alive and used now as they were in the 16th century; goods passing through the hands of the rich and powerful.

I miss my turning and the GPS reprimands.

+

I’d never paid that much attention to Tamsin’s studies. But later into the journey, the thought strikes me that she knows all about mapping and territory. When I see her that evening, I make a point of asking if she knows much about art crime and the trafficking of stolen artefacts.

- Well, art like Camille’s can be used by criminals as collateral if it gets into the wrong hands, she says. The really valuable stuff, that is. “If I can get this painting back for you, you have to reduce my sentence.” That kind of thing.

She beckons me over to her laptop.

- See this.

The image on the screen shows what looks like a piece of scrunched-up, punctured paper. A field of ash that’s had bombs rain down on it. It turns out to be a satellite image of looted antique sites that were once of significant archaeological interest.

- I’m more bothered about things like strip-mining antiquities in places like Syria and South America, she says. When the looters beat archaeologists to it, the historic context of the site is destroyed. There’s no way of re-establishing the stories behind each object.

I immediately visualise Perry’s office, populated by small antique figures.

- I guess it’s a matter of not having the infrastructure to police the sites.

- Yes, but when you’re up against the wire, if you’ve got a starving family to feed and there’s a market for antiquities willing to pay you – admittedly a pittance – you’ll do the looting.

- There’s certainly a market.

- It’s partly why I’m drawn to the artists in ‘This Land is Our Land’. They interact with the earth but in ways that are temporary, non-invasive, exploratory, observational. Look at Sabine Kussmaul’s work.

Tamsin brings up Kussmaul’s website, scrolling through images that show the way the artist scores and marks worn fabric with ink and pencil. Literally binding it to her body as she runs across the landscape.

- She works directly with the land but then leaves it be, respects it.

I’d noticed her work at PAPER; a delicately inscribed scroll unrolled at Kinder Scout and drawn on from sensory observations, then taken out into the landscape once again and used as instructions for a second foray. I agree with Tamsin that it’s kind of comforting to know that artists are joining together to protest about the misuse of the planet and the mishandling of politics. The amplifying voices of those protesting about the dirty money that goes into aspects of art sponsorship; the persistent activism of Extinction Rebellion. Maybe there’s some hope after all.

+

* Carl Einstein gave an oration at Luxemburg’s graveside, the content of which was lost, and Holmes’s book is an edited collection of possible versions.

‘This Land is Our Land’ is an exhibition curated by Simon Woolham & Stephen Walter presented at PAPER Gallery, Manchester, 29 June - 3 August 2019.