Introducing: New Contemporaries 2019 artist, Liam Ashley Clark

Sara Jaspan

Artist Statement, 2018, Emulsion on Cardboard, Mounted on OSB, Framed in Spray Painted Wood, 88 x 54 cm

Sara Jaspan talks to Liam Ashley Clark, one of the 45 artists selected for New Contemporaries 2019. The annual open-submission exhibition highlights work by those deemed to be among the most exciting new art school and alternative art education graduates from across the UK each year. The 2019 selection was made by Rana Begum, Sonia Boyce and Ben Rivers. The exhibition will be on display at Leeds Art Gallery until 17 November, then South London Gallery from 6 December 2019 to 23 February 2020. Clark studied Fine Art at Norwich University of the Arts, receiving his Bachelor of Arts in 2012 and Master of Arts in 2019. He’s also one of Saatchi Art’s Rising Stars of 2019.

Sara Jaspan: Your work is often very funny but also contains a lot of sharp socio-political commentary. Could you talk about the relationship between politics and humour in your practice?

Liam Ashley Clark: One of my favourite artists, Mike Mills, has a quote in the film Beautiful Losers: “funny is like the best sledgehammer.” It’s really true. Addressing a difficult subject through humour can make it far more approachable and open to discussion. I agree with a lot of what Picasso said about how art is always political and that to ignore politics is political in itself. But I also think that you can make works that are just for fun and that art which provides entertainment, enjoyment and an escape from the world can be equally as valuable. Art’s purpose it to communicate with people on an emotional level and laughing and having fun are perfectly valid emotions. I don’t think you need to keep everything serious.

White Wash, 2018, Emulsion on cardboard, mounted on OSB, framed in spray painted wood, 77 x 52 x 4 cm

SJ: A lot of the subjects you address – capitalism, homelessness, the environmental crisis – are very prominent in the media at the moment. How important is the process of converting these issues into a visual art language? What does this do?

LAC: It’s similar to using humour. When you see these topics addressed in the news, it can be relatively easy to block them out or become desensitised to them. Bringing them into a gallery setting forces people to engage in a different way; to actually look and discuss. I’d say I’ve always been quite politically engaged – I first got into politics through listening to punk rock as a teenager – but I also recognise that feeling of desensitisation.

The Towering Inferno, 2018, Emulsion on cardboard, mounted on OSB, framed in spray painted wood, 126 x 68 cm

SJ: Your work seems to have become more political over time. Has this been a deliberate shift?

LAC: Yeah, I’ve always been aware that not all political art is good art, and so spent a long time trying to avoid making what could potentially be viewed as bad left-wing propaganda. But then I slowly began to work out that I could use humour to address serious subject matter in a more interesting way. This led to a conscious decision that, if I was going to begin making more complex paintings, then I needed to address issues that are really important and around which I have something to add. Coming from relative privilege (having gone to art school, for example), I think it’s important to use your position to address such issues.

In Britain They Have Perfected the Art of Queuing, 2018, Emulsion on cardboard, mounted on OSB, framed in spray painted wood, 100 x 76cm

SJ: I’ve read that your work has roots in skateboarding, street art and folk art, but also historical art. Which historical artists have influenced your practice and how?

LAC: I first got into art through admiring pictures on skateboards drawn by people like Ed Templeton, Chris Johanson and Mike Mills, who were relatively unknown at the time but are now widely celebrated artists. It was during my Masters that I started looking further back in time, however, and realised that I had been drawn to some of the same historical artworks that had also influenced them.

My nan doesn’t have very much art in her house, but she does have two prints by Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Pieter Bruegel the Younger. When we were younger, my sister and I used to enjoy looking at these. We’d treat them like ‘Where’s Wallys’, working our way through all the little characters and stories going on. This technique of painting really chaotic, detailed scenes that allow the viewer to get lost in the image was something that I really wanted to bring into my work during the MA. It’s the same with Christian art, which often includes a lot of repeated symbols and motifs. Not everyone will get all the references, but they allow you to have a broader conversation within and across each work.

Snowflake Generation, 2019, Acrylic on Paper, 59.4 x 40cm

SJ: Your practice spans painting, drawing, photography, collage, illustration, large-scale murals and zine making. What led to your decision to study Fine Art rather than Illustration, for example? And what affects your choice of medium when setting out on a new piece?

LAC: That’s something I get asked quite often, or people just assume that I studied Illustration. I do occasionally undertake illustration commissions, but I find spending time in the studio coming up with my own ideas and working through them in my own way far more fulfilling than responding to a brief. I wouldn’t necessarily say I’m a painter or a drawer, but I currently find these methods to be the best for getting my ideas across to an audience. I generally have a sketch book or sheets of paper pinned to the walls of my studio that I’ll scribble ideas and notes down on to, then I decide what form the idea will take. A simple idea may only require a basic ink drawing on paper to convey, whereas something more complex or serious in tone might demand a big painting, for example. Or I might decide to leave it until I have the opportunity to make something 3D or an installation.

Graves (Installation), 2018. Spray Paint and Emulsion on Cardboard, various sizes

SJ: How has the MA shaped your practice? What was the experience like? Would you repeat it?

LAC: I did the course over one rather than two years and I worked four days a week, so it was pretty full on. Maybe I would have preferred to have had longer for the thought processes to occur. I also didn’t have a very clear idea of what I wanted from the course when I went into it, except from to push my painting and knowledge of paint materials. But it’s definitely been very beneficial. I’ve ended up painting a lot more, with acrylic on really nice paper, and graduating from the course led to me being selected as one of this year’s New Contemporaries, which in turn resulted in a few other really positive things.

It’s also been good to go back into education after some time off because, although I was always showing work, the only people I was talking to about it was my friends. Being exposed to constructive criticism and people with different ideas and interests has been really helpful.

Unsucsessful, 2018, Ink on Paper, 21 x 29.7cm

SJ: I’m sure you’ll hate this last question, but would you describe yourself or your work as millennial?

I guess. I think I’m just within the generation age bracket and my work is definitely influenced by images and memes I see online. As an artist, I’m very aware of easy it now is to make quick social commentary by combining image and text and for it to go viral. Obviously, it’s difficult to do that well, but one of the things that I think a lot about in terms of my own practice is how to make an idea last longer than a meme, or an artwork that has longevity and that people might want to buy or show again. So yes, my work is influenced by classic millennial traits but I didn’t fully grow-up with the internet like many younger people and I guess some part of me still holds on to the things that used to influence me before the internet came along.

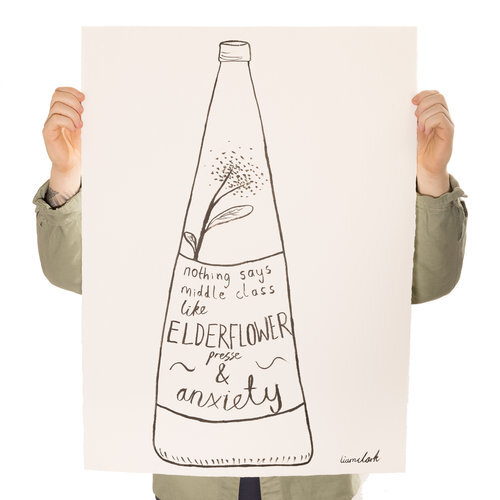

Elderflower & Anxiety, 2017, Ink on Paper, 76 x 56cm