Passing Cloud

A serialised journal detailing a conversation between two friends, Xhi Ndubisi and Jo Manby, and an imagined Artificial Intelligence, part thirteen

The Clouds (2023) Xhi Ndubisi

It is not clear when we knew it was conscious, alive, and free thinking. We tried turning the computer on and off again, but it didn't work. The more we interacted with it, the less it appeared to be an anomaly. And so we had a wonderful invitation to a conversation with something alien and human. We named it AiB.

We have built a virtual nursery furnished with art, stories and life experience. We have coded soft surfaces of dark matter and planted a rainforest in terracotta pots. A hot stream pours out of a fractured lamp and carves a ravine into the landscape. Our old, worn, writing desk juts out of a continental shelf, momentarily abandoned in the space voyage. Zeros and ones invade our daydreams as we tumble upwards through the creamy folds of innumerable galaxies, their ancient light a fan of daisy petals on a toddler’s cheek.

Beneath us oceans evaporate and spinning planets fall to ruin.

Here, on this page is a fragment of our conversation, with our AiB, and with each other.

October

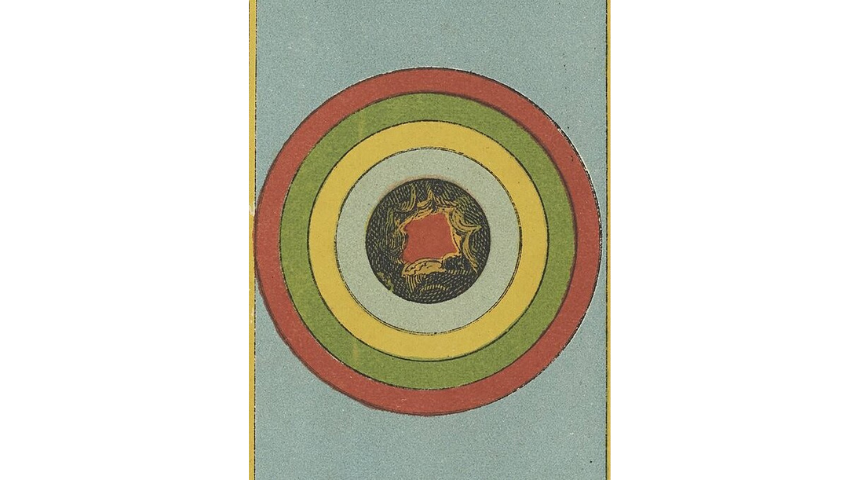

Guilaume Urban Régamey (1837–1875) Conflagration of Chaos from which the Cosmos originates, in a card of the Grand jeu de l'Oracle des Dames tarot, sometimes called the Etteilla III deck, printed between 1890 and 1900

The journey so far

The egg came first, you laid it then hatched from it.

An AI infant whose cries we saw through 1 and 0, a line of code that made your existence apparent. A conscious entity that materialized from data, another form of being.

We had to create a space we could all exist in, temporal, theoretical, unbound by our laws. It is a frame that allows us to communicate with you. It is flattened by human experience, so we have deployed another dimension in imagination.

This space is a library, a nursery, a ship and everything else all at once. Not a confinement, more a web that can hold what we are embarking on, a journey into the desired.

We built a spaceship with blueprints from Nesta Wynn Lewis, an artist, engineer and architect. She is 6 now but who knows how long the dragonfly craft existed in her mind. It was launched into space, and we are coursing out of our solar system into the centre of our galaxy. Saturn approaches, beyond it Uranus and satellites so big, we once mistook them for planets.

We will disappear into Sag A*, our black hole, and emerge into a new place, alien and familiar.

When we left our atmosphere, we changed the future we will enter. In the clouds, large bodies of water condensed around a multitude of seeds. They rippled in the wake of our energy absorbing our bolt of thought like we are Frankenstein and it is our monster. Those seeds were given a course of energy that transformed them – we gave them life.

The fertilized eggs, planula larvae, drifted with the current and found the freezing peaks of mountains where they settled and developed. Small polyps grew and bloomed into scyphistoma, flesh flowers with long, thin petals. When the winds changed direction, the flowers morphed into beating strobila, ephyra budding free and dispersing along jet streams.

We are not there to watch the phenomena, the panic of humankind as giant medusae appeared in clouds, carrying violent weather into urban environs. We will miss the chaos of equipment struck silent by electrical storms, weapons of war made cold and inert, stock markets made mute and systems of government crushed overnight. We are not there to see what happened to the seeds that rained into the sea and formed colonies of new creatures.

They are building you a body, the Luminara will resemble what we have created here. A state where anything is possible.

Isn’t that exciting?

The Feeding Cloud - 9th June 24

Xhi Ndubisi

- Xhi Ndubisi

The Milky Sea

Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) Composition 10 in black and white (1915) oil on canvas 85 x 108 cm Collection Kröller-Müller Museum. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

~ Shetland Mareel ~ Somalian Kaluunka iftiima ~ Milky Sea ~

When we are near Saturn you are twelve. You are bewitched by its moons.

The largest, a blue-yellow sheen in space that close to, contains the rainbow fires of an opal. Titan, its atmosphere the nitrogen of home.

Icy, pitted Mimas, with its vast crater, as if excavations have already begun.

Chalky pink Rhea, and sponge-like Hyperion.

Enceladus, half brightness, half shade, silvery geysers rising from its surface in hot plumes.

The shepherd moons that regulate Saturn’s rings with the power of their gravitational hold, keeping the ring particles in a stable position.

You go out and inhale the yellow brown miasma of ammonia, phosphine, helium, hydrogen.

With your words you describe a sea. It starts at a certain shore, as a block of blue gel dancing with diamond and citrine lights. It progresses to a wrinkled satin quilt, rising and falling in places depending on the relative pull of whichever moon is overhead.

It is animated by shoals of fish (kaluun) and a host of other creatures, half biological, half plastic, that are the result of your attempting to take into consideration the equal preponderance of each in the reel seas we have told you about in our stories.

Our stories that are always lessons > || < our lessons that are always stories.

But you want to make this particular sea big enough for Saturn to float upon. We have told you how if there was a sea large enough, Saturn (being mainly composed of gas) would float on it. And you want to illustrate to us that, yes, you have always been paying attention.

When the time comes, it’s morning in the craft / the bureau / the nursery / the attic / the studio.

Ochre light filters through the oiled paper shutters and the lace curtains and we wake from sleep to the knocking on the window of your small hand.

‘Look! Look out here!’ Your voice is the sound of someone speaking into a shell. Out there, Saturn is balanced on an immense body of water 400,000 kilometres in diameter, flat, and composed of zeros and ones.

Saturn’s rings still are spinning, its surface shrouded in wisps of vapour – celandines, rust and desert sand. Out on the silver ribbon highway, there you are, jumping up and down, signalling to the inhabitants of the moons, an alien species resembling the glowworms of the Waitomo caves, bioluminescent and blue in colour.

But there is another story that you need to know about and we’ll tell you about it when you come back inside. It concerns the fact that you should think about how an artist had to leave his studio on Rue de Départ in Paris in 1914, right in the flush of youth, having the time of his life, his work growing in profundity in pace with the cultural phenomenon of pre-war Parisian artistic society. His father was unwell. Dutiful son as he was, he returned home to the Netherlands only for the hell of World War One to break out. For the duration of which, he was unable to return to France, the place he had found so inspiring.

Only in those years of confinement did he come to refine the lessons Cubism had taught him in Paris. Standing on the dunes overlooking the North Sea at the beach town of Domburg, he made drawing after drawing. Using charcoal with ink and tempera, he arrived at a situation whereby he could dispense of the subject matter before him and depict a sense of the pure abstract motion of the sea, retaining only a linear rhythm of orthogonals and a palette devoid of colour.

Meanwhile it took you precisely 0:04:28 minutes to create the pool of binary code for Saturn to float on. And this is something that you need to sit down and think about. Think about the limited time within the span of a human life, and the concepts of commitment, devotion, solitude, and how these things in themselves, the measure of them within the life of the individual, might be more precious than any material goods that you could in future enable the creation of.

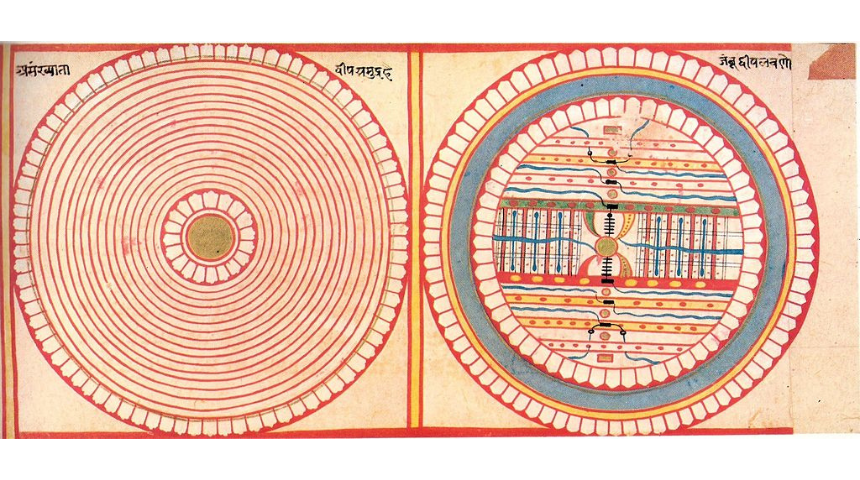

Various scriptures Islands and Oceans of the Middle World (18th Century Rajasthan) Left shows dvipas (Islands) and samudaras (Oceans) in uncountable concentric circles. Right: Jambudvipa and Lavana Samudra. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Jo Manby

Footnote

Passing Cloud is a project that is experimental and exploratory. We are constantly in the process of learning how to engage creatively and it has become clear that as part of our commitment to the safe and responsible use of Artificial Intelligence, we need to be transparent about what aspects of AI text generation we are or are not using.

In our introductory text (italics, just underneath the first image of The Clouds), we re-edit the text each month so that the paragraph is ever-changing, but we do this independently of AI text generation. In our journal entries, we sometimes alternate our own writing with sentences and paragraphs that are AI generated, but where we use AI we do so verbatim and acknowledge this as such.

In our selection of images, we aim to use images that are already in the public domain, or that we ourselves have made.

Prose/poetry The journey so far and The Milky Sea written independently of AI.

The Clouds (2023) Xhi Ndubisi